Image caption

Image caption

FEATURE

Collecting the Looking

“I love drawing really quickly. I love drawing in really difficult situations. I love drawing in the dark. I like what happens when you can’t see everything or when it’s passed and you have to remember it rather than drawing what it actually looks like, so it’s about the experience of looking as much as what I’m looking at.”

We talk to Michelle Avison about building a resilient artistic practice over 30 years.

HAUSPRINT: How important is printmaking in your practice?

Michelle Avison: I’ve been involved in printmaking for a really long time and it’s had a massive influence on my work. I don’t describe myself solely as a printmaker but it informs everything I do and it feeds into all my work.

I suppose there’s a lifetime of choosing the things that I look at and learning how to continue to practice as an artist because I don’t think that’s a very easy thing to do. I think if any of us are making work then it’s a real achievement. The way I’ve managed that is that I’ve found a way of making work about what’s around me. I’ve found a way of looking in order to inform my practice and turn that looking into prints or paintings or drawings.

HP: How did you first come to printmaking?

Michelle: I trained at the Slade as a painter – I went there from what was a very traditional foundation course which was painting in the life room for three days a week, painting in the still life room for one day a week and working in the print room for a day a week. When I first started learning etching I was told to just leave my plate in the acid and go away and come back, and now I say that to people sometimes, because it was almost a revelation to me that my prints could have a life of their own if I let them, and I think it can be useful to try and do that. Then when I was at the Slade I just painted and painted. I was really struggling in my last year and finally plucked up the courage to go into the print room and say “Can I come and do some prints?” They said of course I could and that turned out to be really very instrumental in what I carried on doing after I graduated.

HP: What did you take away from your time at the Slade?

Michelle: I was looking at Pablo Picasso at that time and learning by looking at his prints, copying the way he worked at an image. In his prints the artist or a viewer is looking at the female figure, and that was very much in my mind – that feeling of being female and 20 and learning through living. Looking and being observed and observing that is a continual thread through my work.

HP: A few years later you studied an MMA in Printmaking at Wimbledon School of Arts. What did you do there?

Michelle: I really wanted to learn all the techniques that I could but I ended up doing a lot of lithography with a great artist and lithographer Simon Burder who was the technician there at the time. I started to understand, possibly for the first time, the idea of colour layering and the effects that colours have on each other, which I took back into my painting as well.

HP: What was happening around you that you found inspiring?

Michelle: I can remember very clearly there was a Georges Braque exhibition at Tate Britain and I just thought these things were stunning. They were stunning to me because of the use of colour – very very delicate colours that had an effect on other colours. The way he would deliberately put a colour underneath that would affect the colours on top, not choosing the underneath colour for itself, but as a way to reach the colour he wanted in the final layer. Édouard Vuillard did the same sort of thing.

I was lucky to see an Henri Matisse exhibition in Paris around that time so I was really thinking about colour and colour on top of colour, and then in printmaking terms how you can use colour with as little else as possible, to make the most happen.

HP: When did you first start making work outside?

Michelle: I started going up to Scotland in about 1992 with some friends. Working up there has almost shaped my whole life as an artist, in loads of different ways. I found a place where I could safely sit outside and paint and draw and nobody really cared less what I were doing, so I found a place where I could concentrate and just do it. Living in the city – working, teaching, being busy – sometimes you don’t get much work done, so I started taking a month or five weeks or three weeks or even just a week in Scotland to make work, and have continued to do so ever since.

For a long time I had been painting skies in London, the horizon and buildings against the sky but as I started to paint in Scotland what I was looking at changed. It was that idea of the horizon line with the sky and where those two things meet, where you sort of confuse and lose the distinction between them. I suppose my paintings became more and more abstract because I was responding quickly to the landscape and they were getting less and less detailed. I was also looking at the man-made elements in the landscape in this place where the man-made and the natural join.

HP: How did printmaking find its way into what you were looking at?

Michelle: In looking for shapes in the landscape the works started to be informed by printmaking because I was making compositional decisions about making shapes and finding new things in the landscape that I might make something from. When I look back at some of my much later paintings, they became sparer, and it suddenly occurred to me that the space in the paintings is almost like the space that you get in prints, because you start being aware of the white space of the paper – I think the paintings are doing the same thing.

I was looking at the landscape – it’s incredibly beautiful looking westwards and then you’ve got this village the other way – and I would make drawings and prints between Scotland and London. I made a series of about 20 etchings called the Scottish series. The plates were drawn in Scotland so they were only line drawings and I brought the plates back to London to etch. I expected the line drawing etchings to be really beautiful, and that would be my job done, but they weren’t, they were really dull.

I worked more into them in London, so in fact all of the work on them was from memory really and from what I knew the place looked like. The thing that’s happened as I’ve gone back there time and time again is that I’ve started to build up a knowing of what the place looks like and knowing what I want things to look like when I make them. There’s a real joy in that repeated looking and the way you can draw from that as a thing that always informs what you’re doing.

HP: Can you talk about the connection between the landscape and the making of the prints?

Michelle: All of the tonal work and all of the texture work in the etchings meant they became very physical with very heavily bitten parts of the plate. The process of getting that really deep bite and using the deep etch to make spaces in the print – in the landscape – to bring things forward and to take things back – is such an important thing for me in printmaking. In black and white it works in a tonal way but when you get into colour you’ve got the difference in surface plus you’ve also got the the combinations of what you do with colour and where you put it. And with printmaking, because you have to consider what you are doing, and the order you do it in, you have to make it work with as little as possible, so it really informs my painting as well.

Again in a later series looking at small rock pools I only drew the lines and then the etching process put the rest in place. It’s the letting the plate have a life of its own that really makes the images happen. I want to make certain things happen but I also live with the accidents and work with the accidents and perhaps deliberately make accidents happen, so the plates and the images have a life of their own.

HP: The print process lends itself to series-making, but what does this mean to you?

Michelle: I’ve always been interested in the idea of pairs of images or groups of images or series of images. What I am trying to do in the Scottish series and the rock pool series is to compare surfaces and differences. They have a sense of travelling or passing across the landscape, where I see one shape and then another, or I see the same place over and over again, but it’s changed because the light’s changed or the weather’s changed or I’ve changed in the landscape.

HP: How does that sense of place travel from Scotland back to London with you?

Michelle: In around 2012 I started to make prints in London that I thought of as urban rockpools, deliberately putting two things together which are urban, like a hole in the concrete in the yard outside next to an image drawn from the studio floor. I was really trying to find my way into understanding where I was then working, because we had just moved into the Haus Print Studio. For me, drawing and looking and recording what’s there right next to me is how I find my way into making work, so that was what I was doing at that point. I was looking at the yard outside and I was looking at the concrete inside and I was making images about that. I was looking at them in exactly the same way I was looking at things in Scotland.

HP: What do you mean by this?

Michelle: I’m always looking for the same things and what that throws up is the most interesting thing for me. Things start to have the same qualities. It’s not necessarily about the rock pool in the landscape (although it can be) and it’s not necessarily about the puddle in the pavement (although it can be). I’m looking at the shape of the rock pool or I’m looking at the texture. It’s about the distillation of looking. I am learning about what things look like by looking at them more and more.

Living in London and then travelling outside London I am very aware of different landscapes. It’s often very beautiful outside London and it can often feel not very beautiful in London, but I think the more that I look at things, and the more that I look at the minutiae of things, the more beautiful they become. Even the pavement is beautiful to me. There are things there that I want to look at just as much as that west facing landscape in Scotland.

HP: How do you work when you are in Scotland?

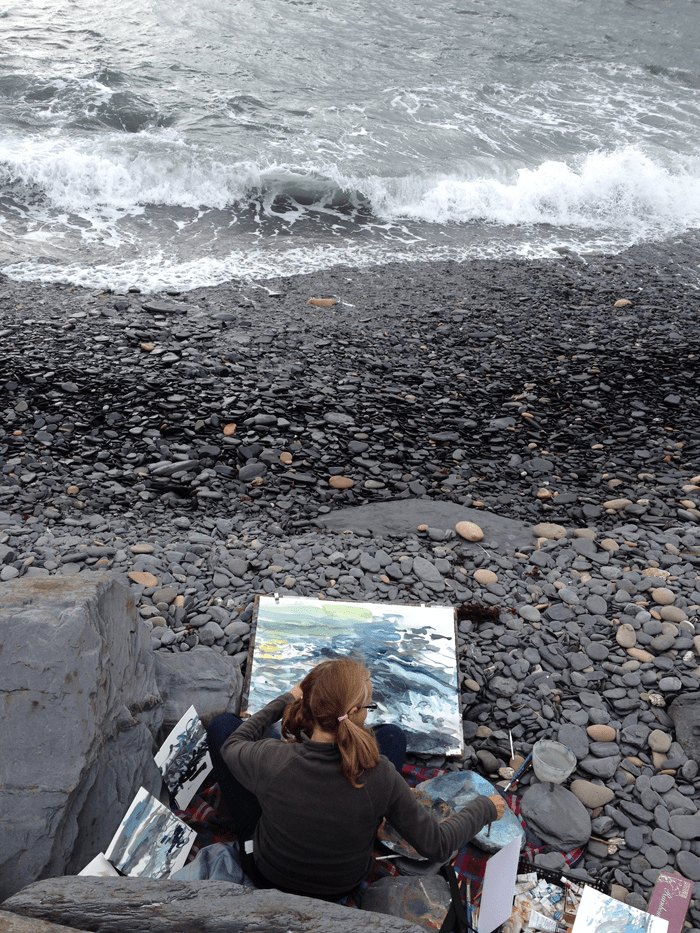

Michelle: I go and I’ll sit on the beach for hours on end. I’ll sit there in the rain or the dark or whatever. Obviously looking at the sea and responding to the sea is a massive part of that and it’s an exciting thing to do, so I’ve done loads of paintings of the sea over the years. I force myself to work quickly, force myself to record what I see, force myself to invent the colour, to make the colour respond to the experience of sitting there trying to paint the waves coming in. It’s an impossible thing to do and I do it over and over again. I might make 20 paintings over a couple of days.

It’s like the action of trying to paint in that situation starts to make the painting do something else. One painting’s got stones stuck on it because I probably just dropped my brush on the beach and the stones got stuck in there. The paintings are very visceral. They are a visceral response, and come right back to my printmaking and what you can do with different surfaces. For some, I just picked up pieces of wood that I found and I sloshed some ground on them to use. I decided not to cover them completely with ground because I wanted to respond to the colour of the wood.

HP: How does being a printmaker affect how you look at surfaces?

Michelle: As a printmaker I’m so aware of surfaces, like with a new piece of metal or a piece of wood or a litho stone. They become really important in what you’re doing, so if I’m making a woodcut I’m really aware of those knots and the bits of the wood. The same with the paintings on wood panels – I didn’t want to lose the knots, I wanted to include them and the colour of the wood in the image. There’s some gesso in there but there’s a piece of chine collé of a rubbing. I’ve made rubbings for years and and I suppose they are a recognition of surfaces and what I see as a printmaker, the things that get me excited, and then I’m always trying to incorporate that into that painting.

There are elements of collaged rubbings which have been made there in situ but also for a few years now I’ve been taking rubbings back to Scotland that I’ve made in London. It’s become something where the surfaces – like the tarmac or the pebble surface or the rock surface or the piece of wood – are part of my life, and then they start to not be one thing or another, and in the work you might lose sight of which is the man-made and which is the natural. That interests me a lot.

In another series of Tide works (I don’t know if they are drawings or paintings, but they are drawings to me I think), I’m using materials to try and work with the wood, and that’s so like what you do when you’re making prints, you have to respond to the surface of the material that you’re working with. I’m responding to the material when I’m drawing and I’m using what I think I need to use to draw what I want to draw, so I’m picking things up quickly and using them to try and capture what’s going on when that tide’s coming in or going out.

HP: What drawing and painting materials do you like to use?

Michelle: I tend to just carry a massive bag of everything with me when I go to Scotland these days, anything I can get my hands on really. In the past I often picked up children’s crayons because they were the only materials I could get locally.

I think materials have become really important and my choice about what I use to give myself the repertoire to capture what I want or to be as honest to what I ‘see’ as I can be. I don’t mean ‘see’ in a figurative way, I mean it in the broadest sense.

HP: How do you decide what to draw?

Michelle: I made a very deliberate decision to try to draw the sea the tide at different times and I went to the same place at the top of the beach at the same time every day and did a drawing. One of the things I have done quite often and continue to do is I sort of set myself something I have to do, or a project I have to fulfill, and there’s something about going back to that same place which helps that process. I can think okay, I’m going, and when I get there I’m going to do this, this and this. In my day, I marked my day by going up to the same place at the top of the beach and drawing the sea every day and just seeing what I see. It’s almost taking the decision making out because I’ve made a decision already, to go there and draw whatever I see, so it makes it easier for me just to get on with it.

HP: The sea is such a big subject. How do you approach it?

Michelle: Going back to the sea and the movement of the sea, the repetition of it coming in and out, the corrosion that it causes, the moving around of the landscape caused by the sea, I’ve looked at that and drawn that for a long time. I’ve drawn the seaweed on the beach where it’s thrown up. I’ve drawn the stones where they’ve moved. I’ve drawn plates looking at the tide coming in and out and then later on I started just sort of throwing the plates down, throwing stones on them or trying to abrade them in some way to to replicate what was happening with the sea. Later I left the plates in the sea to be completely drawn by the sea.

I’ve probably got about 25 plates drawn by the sea over six to eight years. Every year I take a few hard ground etching plates with me and I put them in the sea and see what happens. They get scratched they get moved around, they get lost in the sea and they come back. Some come out like Turners or something – it’s quite extraordinary I think. Other ones are like looking in those rock pools, they’re like looking at that concrete, they’re like all the little bits that are in the world are all in these images.

They’re not all the same size or the same shape but they are part of that process of engaging, of responding to being there on the beach looking at the sea, living it, trying to feel my way into what it’s doing. A little set up on the beach and monoprinting, drawing, responding to the tide coming in. It’s six hours of the tide coming in, and as it progresses I find different things I can do, so the print process and printmaking comes into this.

I usually have water-based inks with me and one year as the tide came in closer I was getting wetter and then suddenly it was like “Oh this is amazing!” because I started getting the splashes of the water on the plate and because they were water-based inks I could then print from them, so it was a real revelation, a really exciting happenstance from printmaking, which I’ve continued to use.

HP: Have you ever lost any plates to the sea?

Michelle: I’ve had this a couple of times – I’ve lost a plate for a day or I’ve lost a plate for a few days but I’ve always found them – except for one particular plate that I never found again. I just lost sight of it and the water pulled it out. The following year I was talking to a neighbour there about that plate that I’d lost the year before. Next day I was sitting in the window of the little cottage that we stay in there and he knocked on the door, and he said “Is this your plate?” He’d been walking on the beach, found it, and recognised it because we’d had this conversation the day beforehand. He found it a year later, which was quite nice.

HP: Would you say drawing is the foundation of your practice?

Michelle: I wanted to talk about drawing and going back to trying to find a practice. In the late 1990s and again a few years later when my daughter was born I really struggling to find a place where I could work. The place I found where I could make work was when I was on the move, so I started drawing when we were in the car or on the train, even with her with me on the train. When we were travelling I was drawing on old index slide cards with artists’ information on them. There was something really lovely about picking them up and looking at them and drawing on them. The thing that I like about this is that I’m able to respond to what I’m seeing, it’s fun, and I’m building a way of drawing that works for me.

I love drawing really quickly. I love drawing in really difficult situations. I love drawing in the dark. I like what happens when you can’t see everything or when it’s passed and you have to remember it rather than drawing what it actually looks like, so it’s about the experience of looking as much as what I’m looking at. It’s about passing through the landscape and trying to understand it in that way.

Another little drawing project I set for myself in Scotland was to stop at every passing place along the road of the island and draw in a sketchbook – when you cross a narrow road there are these places called passing places. And just being there in the moment, wrapped up or not wrapped up on an amazingly sunny day, just drawing.

HP: Do you incorporate photography into your work?

Michelle: I take a lot of photographs but they are never actually the work. I think I take photographs like I draw, so I’m trying to find information that adds to the other information that I have, in urban rockpools or Scottish rockpools or wherever. I’m looking for those same sorts of combinations of shapes and colours and textures so I can then play with the confusion of those things in the print, finding shapes in the landscape.

HP: Do you ever use your work as reference or starting point for new work?

Michelle: I have started to revisit my history of making prints, including rubbings from rocks and elements from previously printed pieces of material in new work. Coming back in are elements from little etchings and from wood cuts, so there are layers of all the looking I’ve ever done, on different surfaces and across all the different media I work in.

HP: Sketchbooks are a really important part of your practice. Can you say something about that?

Michelle: I always take stacks and stacks of sketchbooks with me to Scotland. I always take stacks and stacks of things with me and I force myself to use it all before I leave so I’m working faster and faster until the time I leave. There’s something really liberating in just saying okay I’ve got six sketchbooks and I’m going to fill them all before I go home. It makes me do it.

I also make sketchbooks – I made a series of sketchbooks to deliberately take rubbings and draw in that way. Again, constructing the sketchbooks so that I’m forced to fill them.

HP: How do you develop ideas from your sketchbooks into new prints or paintings or mixed media work?

Michelle: I had an amazing sketchbook made by Fabriano with this fantastic transparent paper, so you see every drawing underneath and beyond what you’ve done. That became a starting point for a set of monotypes taken from that particular sketchbook, an accumulation of looking at the sketchbook. These prints were made on the press, they’re made like paintings almost. I make a layer, I respond to the layer on the press and I put the next thing in, so they’ve got cardboard relief elements coming in, they’ve got chine collé elements, they’ve got previously printed elements and they’ve got a line linking them together – a line that comes from the sketchbook drawings. The shapes of the chine collé and of the cardboard are a part of that process as well. I had a number of those particular sketchbooks and they all had different colour covers. The colour was so fantastic that that started coming into the prints too, so it wasn’t just about the rock pools it was about the sketchbook itself and the experience of re-looking at the sketchbook and where those prints came from.

I called this series Re-pools, so they’re from rock pools and drawings of rock pools, but I felt like I was reinventing the pools because I included elements of things found in London, and pieces of print that I had made deliberately to put back into these prints. The chine collé is sometimes ‘invented’ chine collé, so I print it or I draw it ready to go into the print as part of the process of bringing drawing and printmaking together.

HP: How did making the monotypes help your practice move forward?

Michelle: I took back to Scotland the idea of the monotype process, so I tried to make work in the way that I’d constructed the monotypes and I made a series called Road-pools. In them there’s paint, there’s charcoal, there’s drawing, there’s pieces of printed material, there’s rubbings of surfaces including some some man-made surfaces that I’d rubbed in London. It’s like my whole life in a piece of work.

I really do think that the paper and the shape of the paper and the way in which I’m putting pieces down in this collage way really comes out of my printmaking because you think in flat bits in printmaking.

HP: Can you talk about puddles for a minute?

Michelle: Drawing and looking at the puddles has been this massive thing for me in Scotland because it always rains. I was talking to Graham who lives in the cottage in one of my paintings, and he was asking why I like to paint the puddles (he has watched me paint puddles for a long time). Behind where I was standing is the beautiful west-facing sea – and of course this is great to paint too, but there is something more interesting to me at the moment in painting the bits that people don’t generally paint. And, in Scotland, you have to embrace the puddles – so it’s something about painting what you find, and when it rains a lot the puddles are what you get! Then, in the end, they look like rock pools and I like that also. Graham then said something nice, which was that when it is rough the puddles become sea anyway as it comes right over the top and fills the puddles.

HP: Which artists do you find inspiring now?

Michelle: Robert Rauschenberg is a big influence, just finding interest in the mundane and the normal. I love his collaged and painted sections, the sequences and repetition and overlaying. The way in which the composition is designed by putting putting these elements against each other.

Also an artist called Jon Schueler who worked in the ‘50s and early ‘60s on the Sound of Sleat further up in Scotland is very instrumental to me. He was one of the American abstract expressionists, he studied with Clyfford Still, has a really beautiful way of reducing the looking down to very little.

I love the idea of place and things in place so these wonderful winged wind combs by Eduardo Chilleda and all sorts of aspects of his work. He was a great printmaker and he did a lot of cut paper things, all things that are really interesting, and his sculptures on the coastline in Spain in San Sebastien. The Boyle Family, they would reconstruct what they found at a place in the landscape, painters like Morandi and Matisse, I mentioned him already but I remember that exhibition years and years ago and being struck by how much he didn’t paint, how much he could reduce the objects to very little, to the spaces, to abstract forms. And then Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a real master at exploring what the landscape actually looks and feels like to be in, and absolutely brilliant drawing I think.

In summer 2020 I decided I’d paint in the car rather than just drawing in the car on our way down to Somerset. David Hockney‘s done that sort of thing I think, driving through the Yorkshire landscape, and I’m from Yorkshire as well so they’ve got a big resonance for me. And looking at Andy Goldsworthy’s sheepfold drawings, whilst I’m not mad on the drawings, there is this idea of locating something in the landscape, locating it again and drawing it again, finding the same thing in the landscape and going back to it – I find that really interesting.

I love Richard Diebenkorn’s work and his exploring of the topography of the landscape and the abstraction of his work, still based in reality but abstract and beautiful. Just that idea of letting the print come into the work, the process, the making of the print, the fantastic things that happen in the accidents of print, all being apparent in the work

Then there is Hamish Fulton, and this idea of exploring a place and telling me about that continued exploration of a place, looking at it in different ways, and writing alongside imagery – I’ve more recently started noting down in writing sounds and things that Ii’ve been hearing and looking at as well.

I really like these Christopher Le Brun prints because they respond to the surface that he’s working from, they’re scarcely print – in that he’s done little work on the blocks themselves, he’s just responding to the blocks.

HP: You have recently started bringing people into your work. Was that a conscious decision?

Michelle: In 2020 I was invited to go to a place in Scotland called Cardross, to Saint Peter’s Seminary, it’s a derelict concrete building and I made some rubbings of the concrete – it’s like the South Bank where the concrete’s got wood effect in it, absolutely brilliant. I made some sketchbooks and went up to the place which by chance is just off the road that we travel up to go to the island so it immediately had huge resonance for me. I started drawing on the train and I didn’t stop till I got off the train when I got home again. I filled the sketchbooks with different ways of looking at things – one was about purely listening, noting sounds and things that I saw. Again this was my way of thinking my way into what I might do when I got there but also just telling myself to do something.

When I got to there people had got inside the building and graffitied on it. I found this piece of graffiti which was actually trying to draw what they saw inside. I thought that was absolutely stunning.

I’ve never really drawn from photographs but I found some amazing footage on YouTube from when the place was still in use, so I took screenshots of the priests and the spaces of this amazing derelict building. I took screenshots of the whole screen and the composition of the screen view, with the playlist and the window tab, which became quite important later. They were the starting point for some prints that included imagery taken from those screenshots and the wood pattern that I saw on the concrete and the rubbings that I took. The wood came into the print as a soft ground texture in the etching but then I also printed from a piece of wood in the background as well. It felt quite weird bringing figures back into the work, thinking back to that Picasso copy that I did at college, because I’ve spent years not drawing people and suddenly people started coming back into the work.

HP: Perhaps because you can’t think of a seminary without thinking of human presence, in quite a deep way?

Michelle: Those prints definitely relied on the way I looked at the landscape and the way I responded to that landscape, where that funny place was in the landscape. One was actually a drawing of a priest from one of those screenshots but it came out looking and feeling like graffiti with guys in hoods. So I was playing with what happens when you draw and when you respond to something and just go with it when it does something else. That comes out of printmaking – learning to live with that accident. There’s a print in the Cardross series relating to the trees that you saw behind the Cardross seminary, so I was thinking about those trees and the line of the concrete but the trees in the print are drawn in the yard outside the studio in London, so they bring the set of prints back to me and my place and where I am.

HP: How did COVID change what was happening for you?

Michelle: I was working on these and then we got locked down during COVID. My Dad was very unwell in hospital and I started to draw him from screenshots that I was taking of him, when I was talking to him on Facetime, before he died. Some of the prints I made in the Cardross series ended up having my Dad in them, from the drawings and from the photographs I took on screen. In the end I always come right back around to that idea of viewing and being viewed. There is the screen, a screenshot of the screen, me in a little screen looking at my Dad and me reflected in the screen. That’s me.

Additional references

Simon Burder Introduction to Lithography: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TkY2PzAn51A

Michelle Avision artist talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8gotyIvc7Y

More Features

All featuresCarborundum

Abrasive carborundum grit (silicon carbide) is mixed with acrylic medium or glue and painted onto a flat surface, such as plastic or metal.

New name, new website

When we set up SLAUGHTERHAUS Print Studio in 2010, we named it after the building. Redesigning our website in 2024 was also the perfect time to launch our new name, HAUSPRINT.