FEATURE

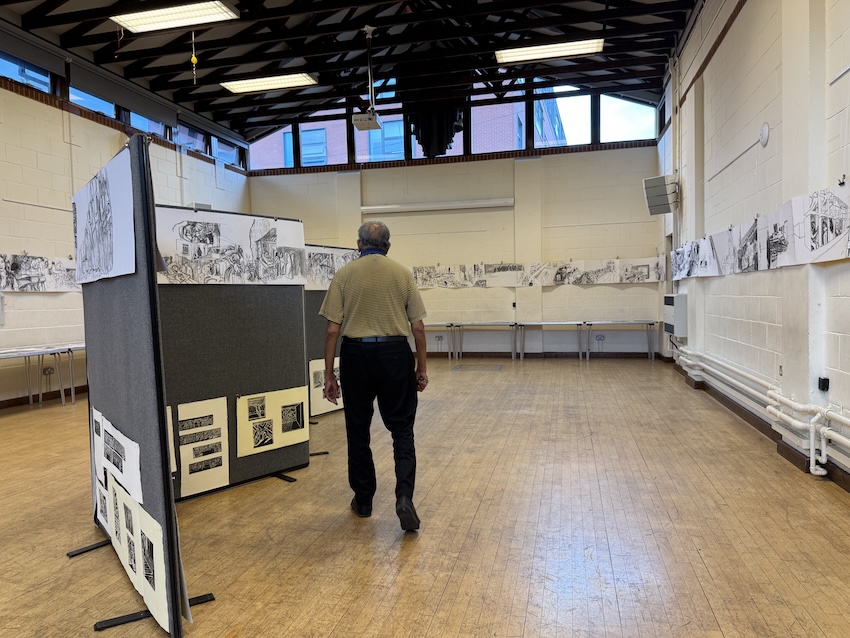

“They’re not simple images. They are about everything.”

Artist Chris Christodoulou grapples with the complexities of life in his epic drawing series Odyssey.

Sarah Gillett: Chris Christodoulou is an expert artist, drawer, printmaker, architect, sculptor, installation artist. He’s brilliant at everything that he puts his hands to, I think. He is always drawing, whether it’s at the South Bank observing everyday life, or at home with his family. Even his sleep provides inspiration as he also draws his nightmares… Chris, when did you start working on the Odyssey series, and why?

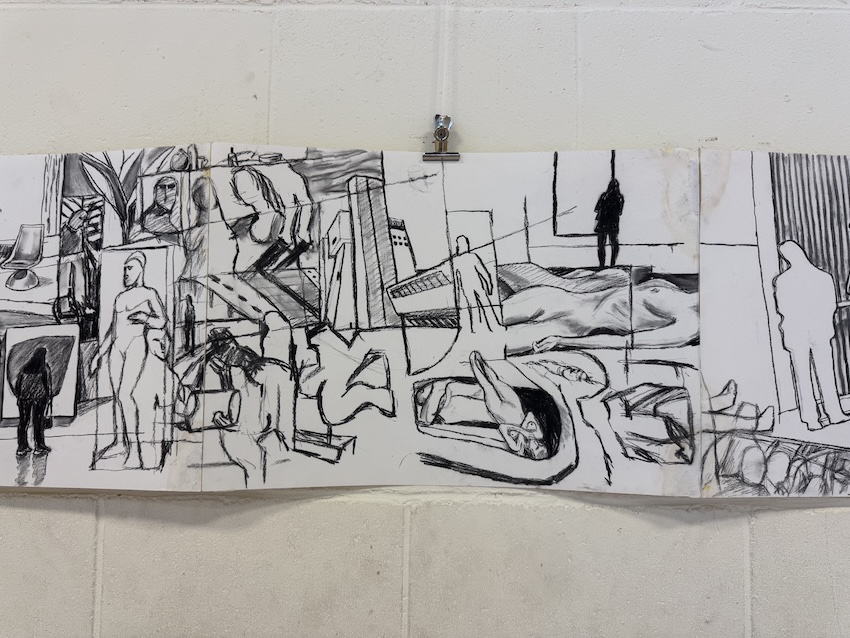

Chris Christodoulou: Well, about two and a half years ago, I think post-Covid, you know, the world changed somewhat, and I recall at the time my life felt really cluttered. That was the word that I kept using when people asked, how are you? I felt cluttered and hemmed in. It just seemed to me I couldn’t move. Everything around me seemed to close in, and my flat was the most, the biggest clutter of all.

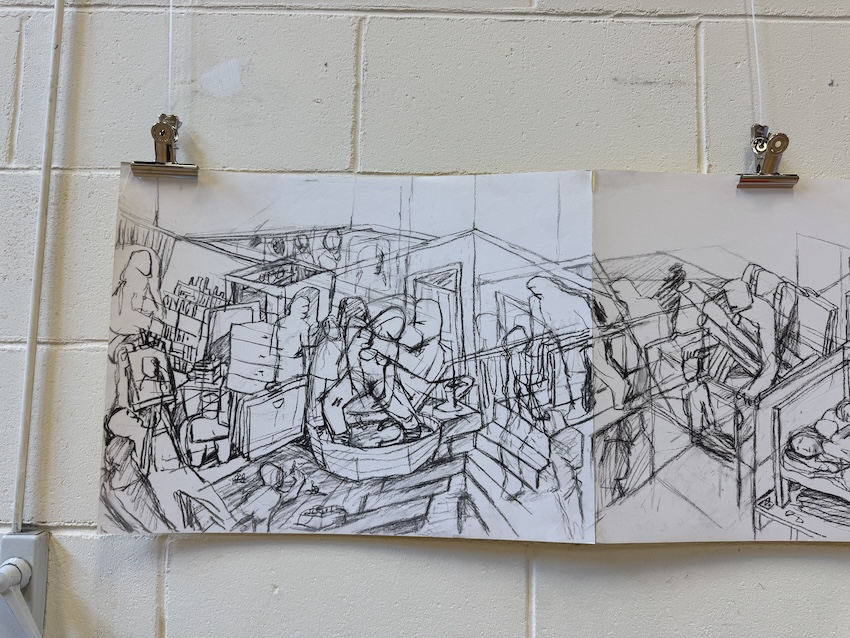

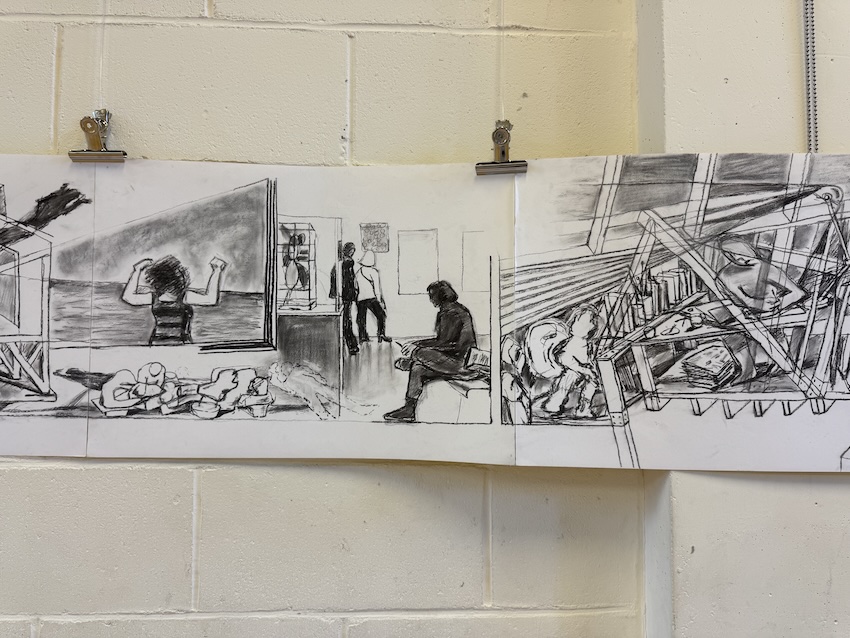

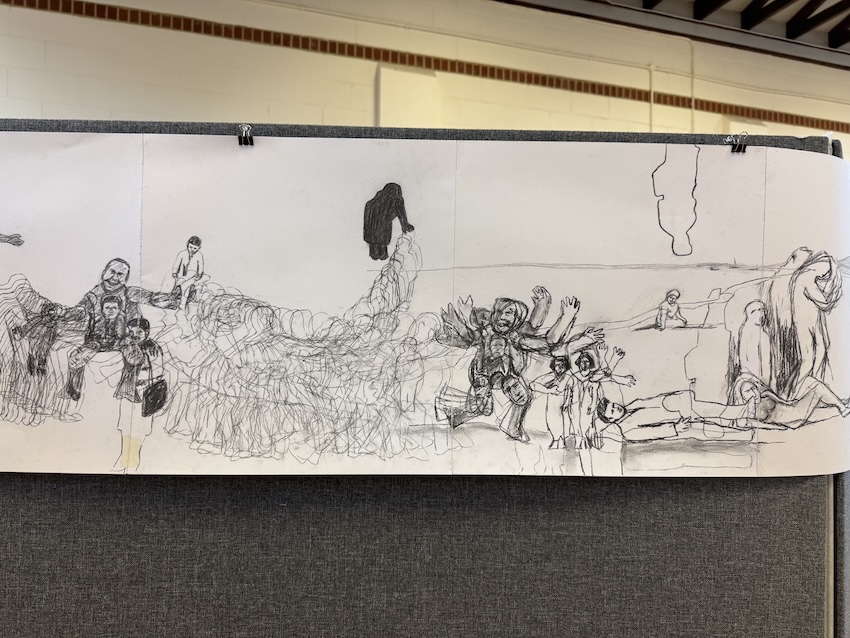

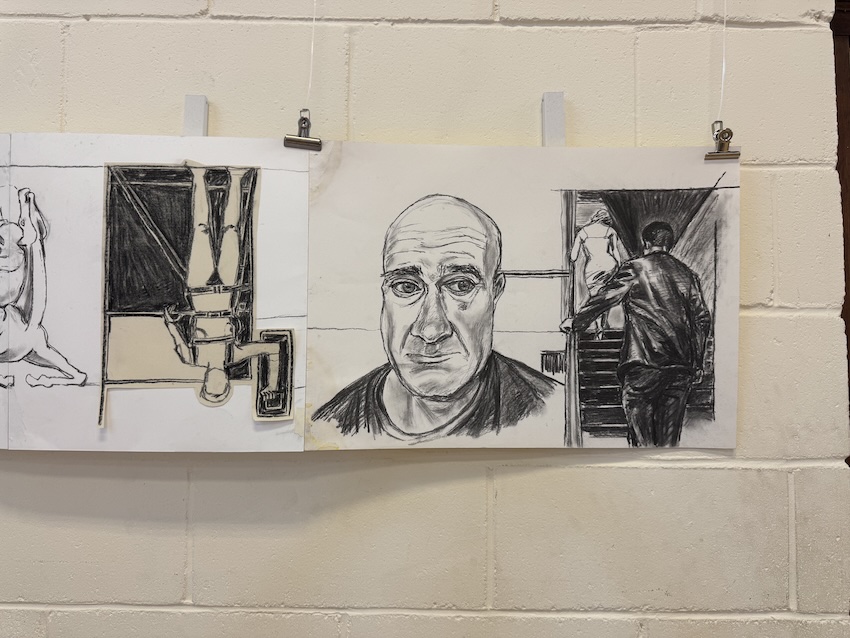

In a way, it kind of reflected my mind. My mind was like the flat. I almost felt the flat was inside my head, so I thought, how can I represent this feeling and try to deal with it? I started sketching the first sketch of what became the Odyssey series, which shows me with portfolios and all sorts. Some of the figures in it are from dreams, so I kind of represent the dreams. That’s how it began.

SG: I can see that you draw with charcoal – charcoal can be a really difficult medium to work with, but it’s a material that you’ve used for a long time, isn’t it?

CC: Since being a child, really. I started using charcoal because charcoal was very much an intuitive process without feeling too precious about the work, just a way of almost like visual association. It’s allowed me a spontaneity. You can do that with words, but visually charcoal allows me that freedom to flow into images without feeling too finite and detailed about it.

There’s a darkness as well and the process morphs things into other things. It allows me that transition, so if I’m thinking about something I can allow the charcoal and my hand movements to move into imaginary scenes. The drawing becomes a journey of exploration for me.

“I’ll only stop when I feel it’s not saying anything.”

– Chris Christodoulou

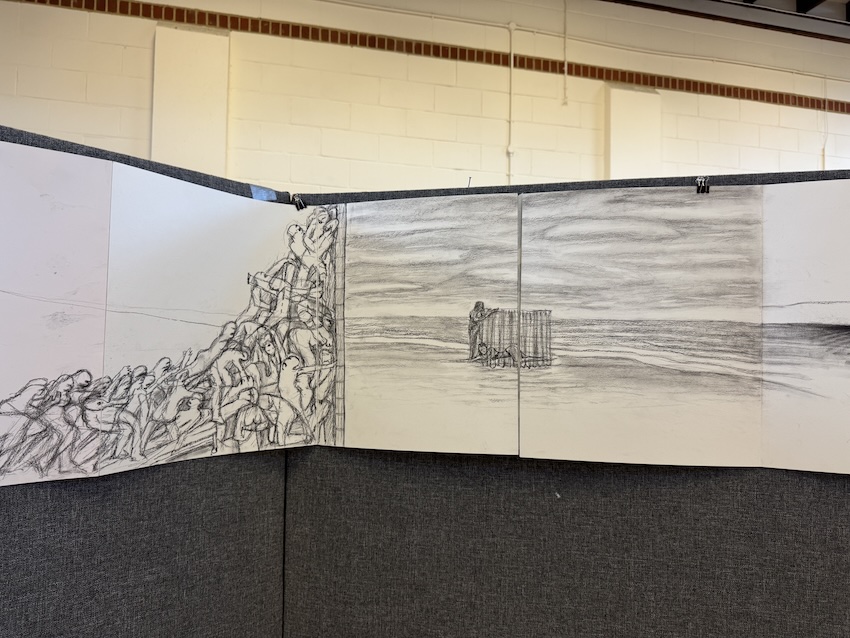

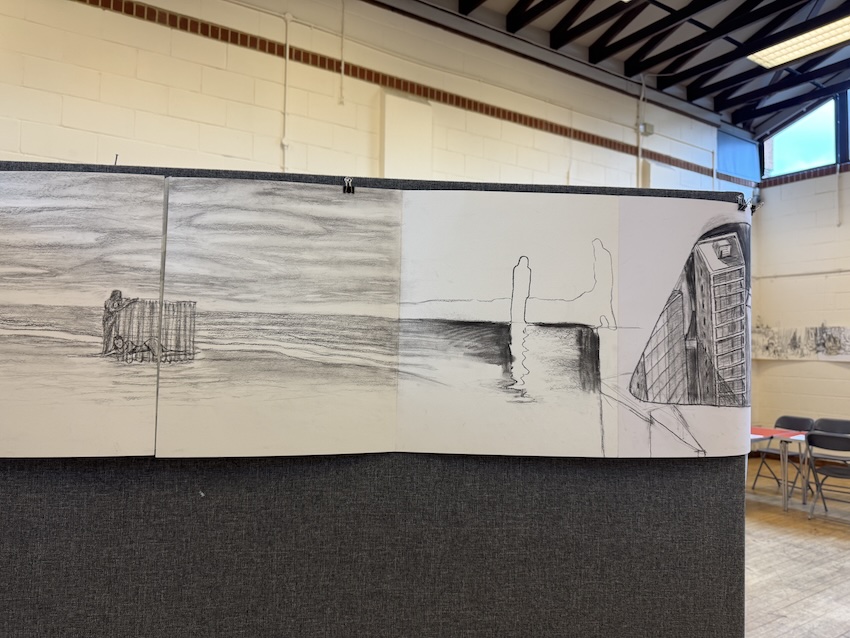

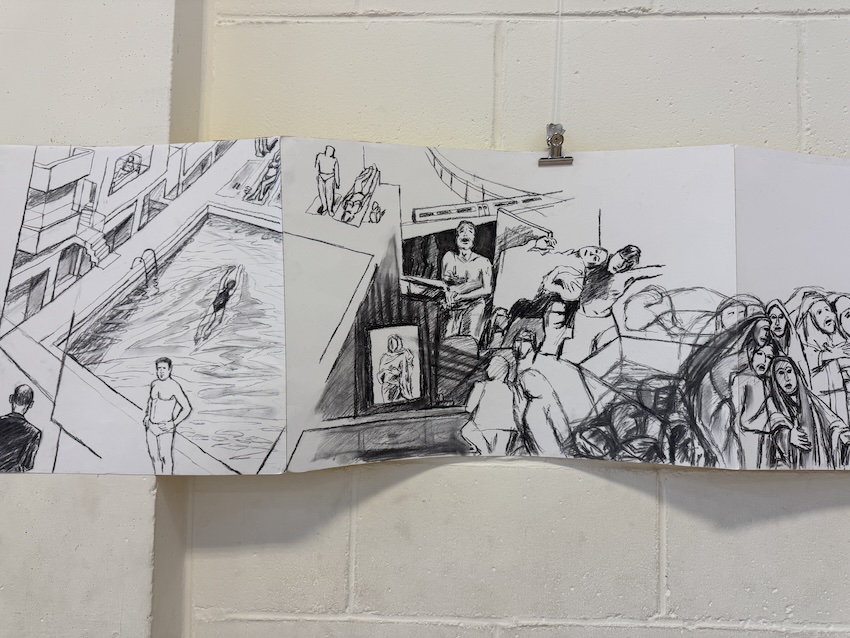

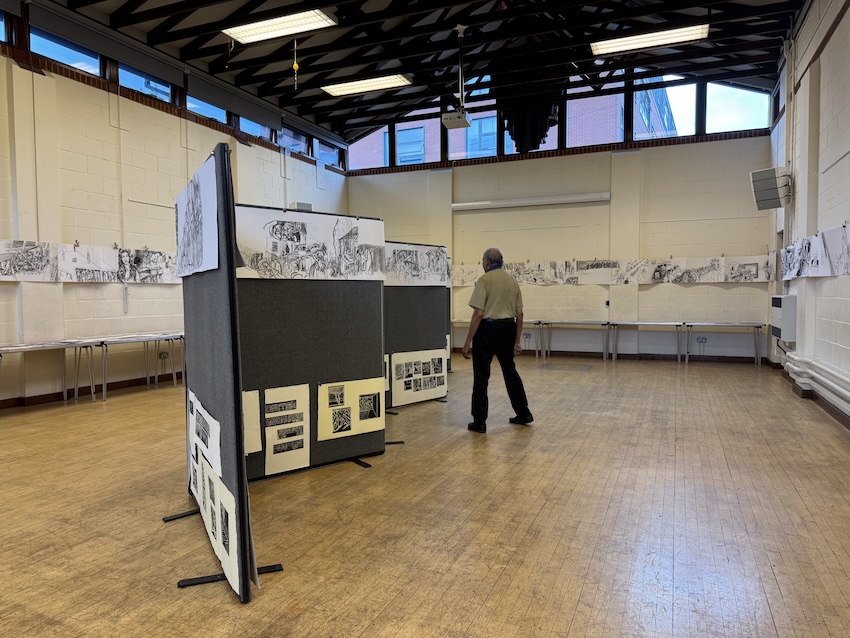

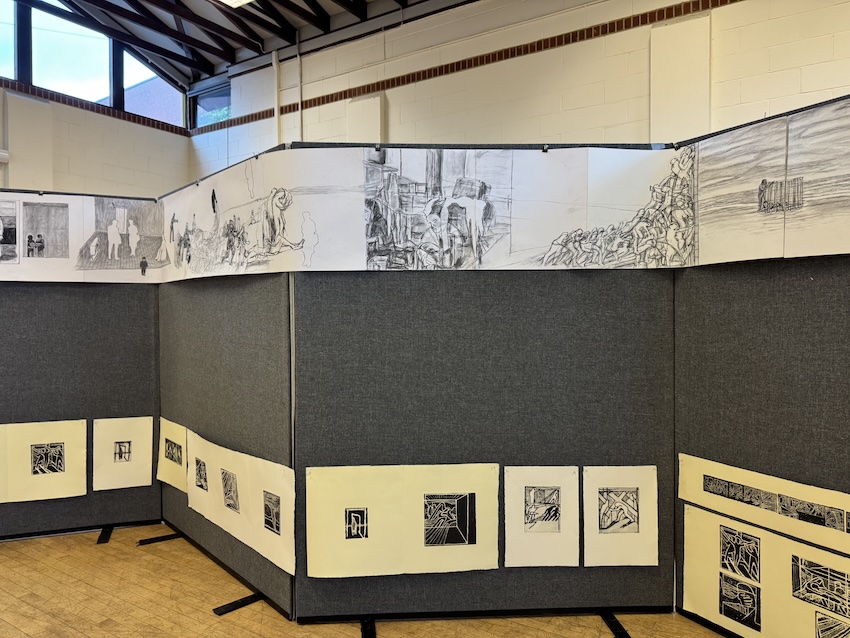

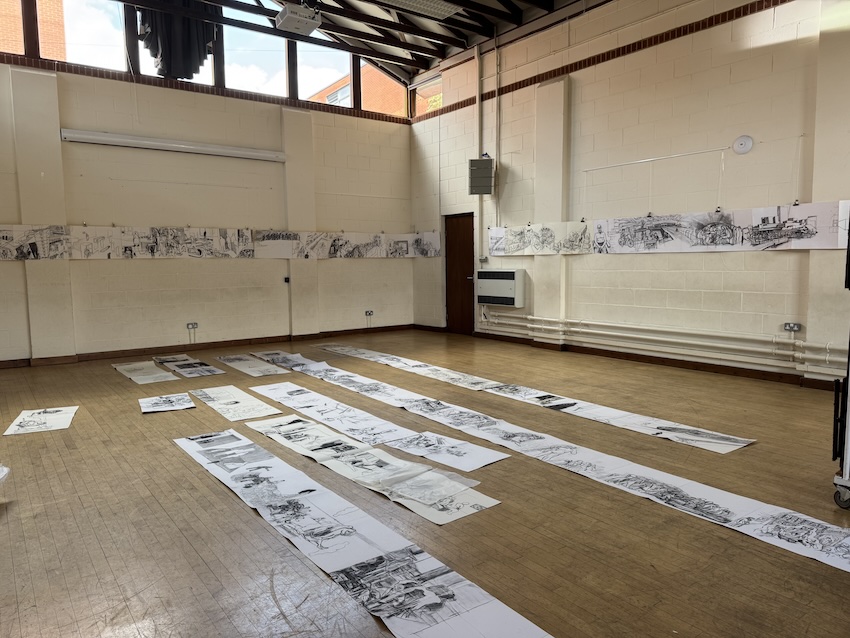

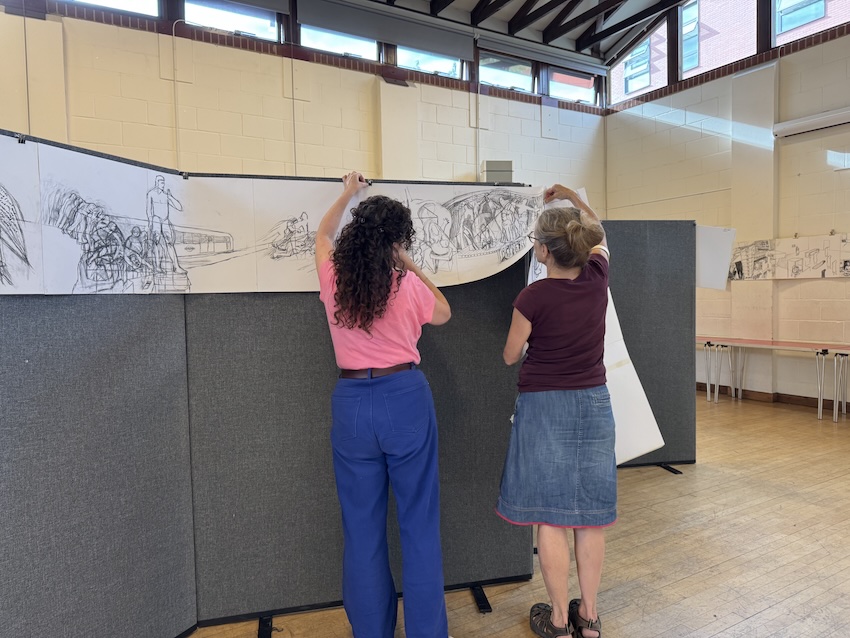

I’ll be working on sections of this series once or twice a week, about three A2 panels at a time. Depending on what happens during the week, I’ll join them up and then the story carries on, so there’s a continuity for me. It becomes a device for telling a kind of visual diary as I’m going along, and it gets submerged with lots of past events, and things that happen, like loss, and the memory of those.

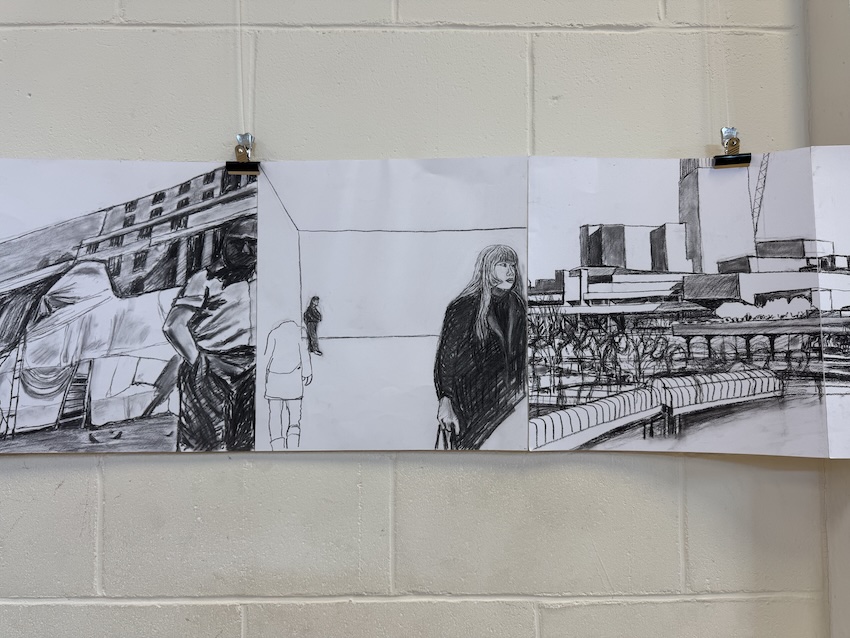

And this notion of home – I’m forever looking for this idea of home. Home like a sense of belonging. So always trying to find a place where I feel… that’s always an ongoing search. Never quite getting there. And the drawing is part of that exploration, really.

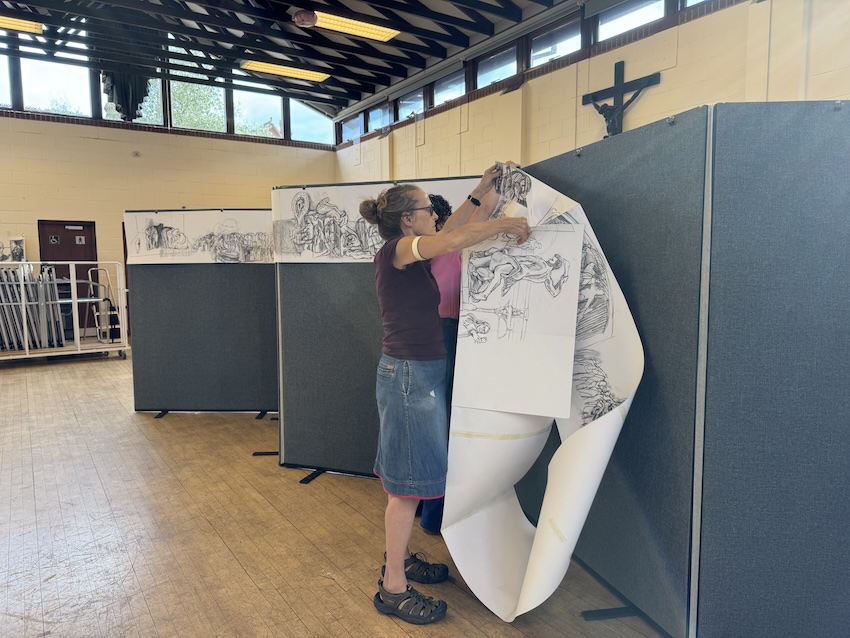

SG: A lot of these themes come up often for you. You started here with this first drawing that we see behind us. How did the imagery develop while you were working on it? The physical process?

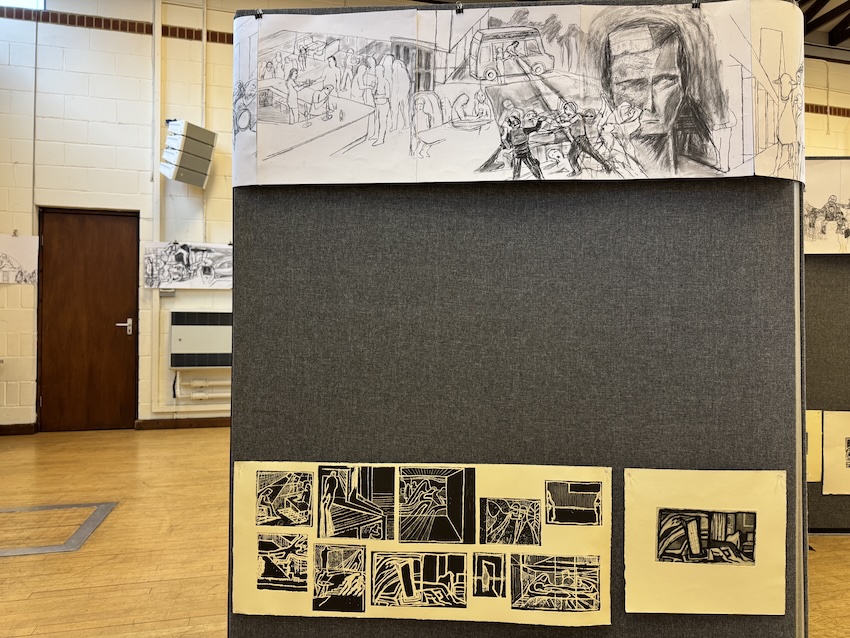

CC: It started off being quite rough, very kind of loose, almost like a shorthand of trying to represent what I was feeling at the time. But then as I developed the pieces, they became a bit more graphic.

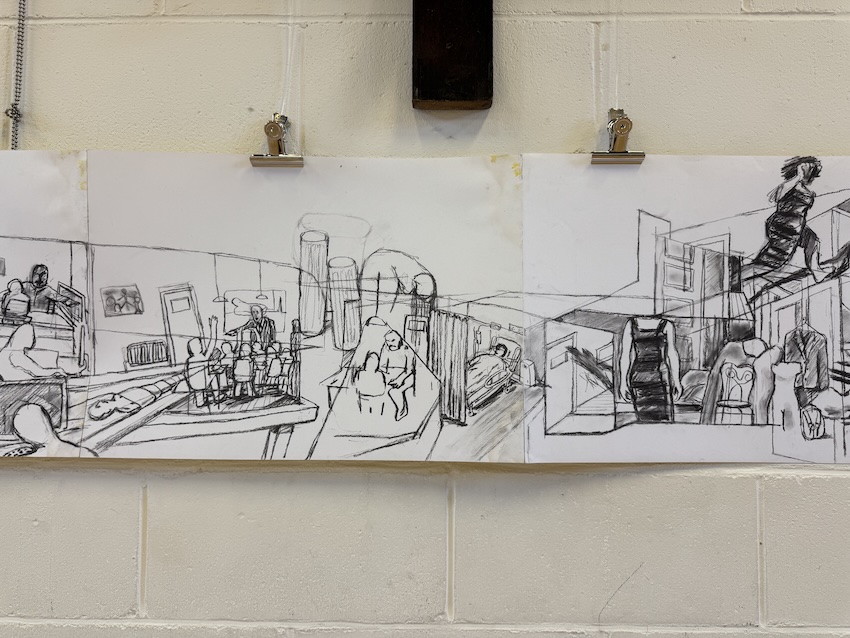

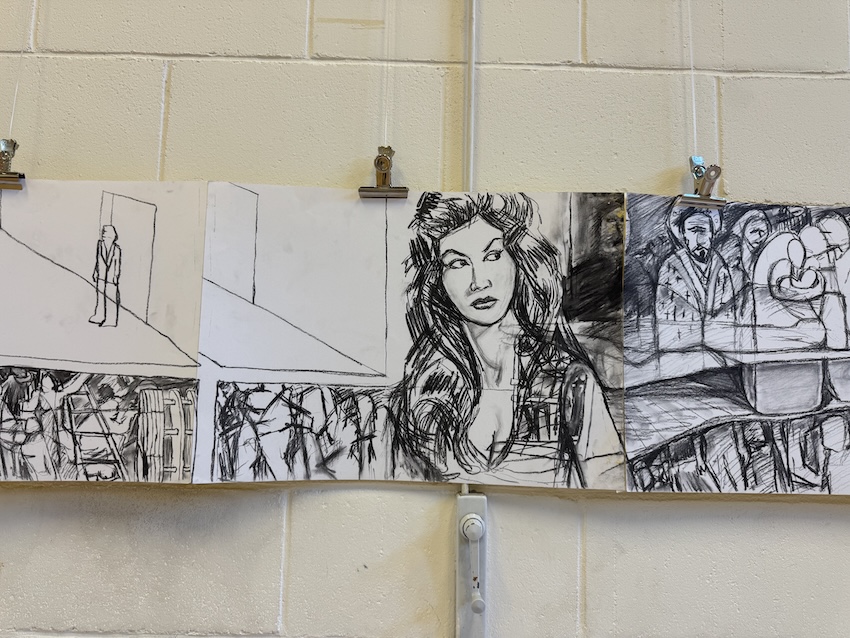

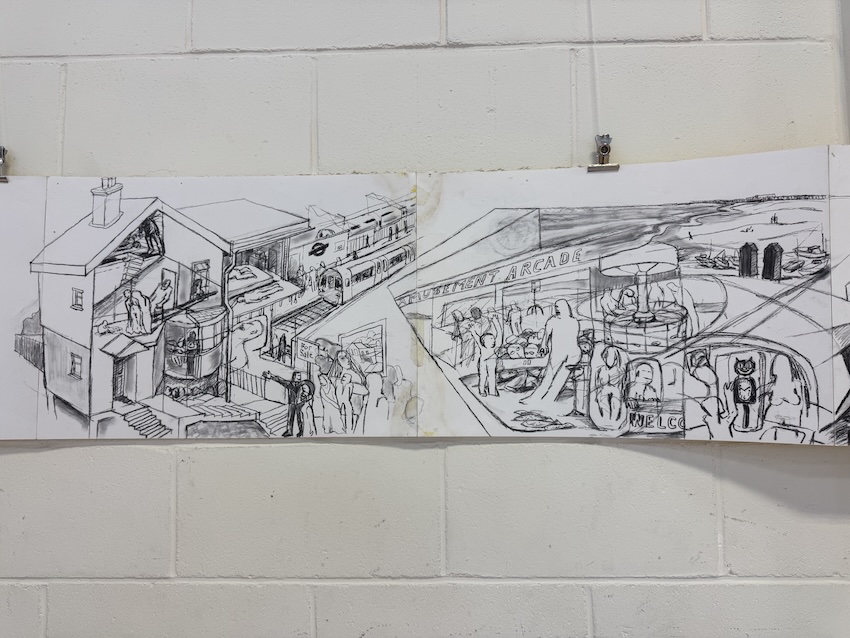

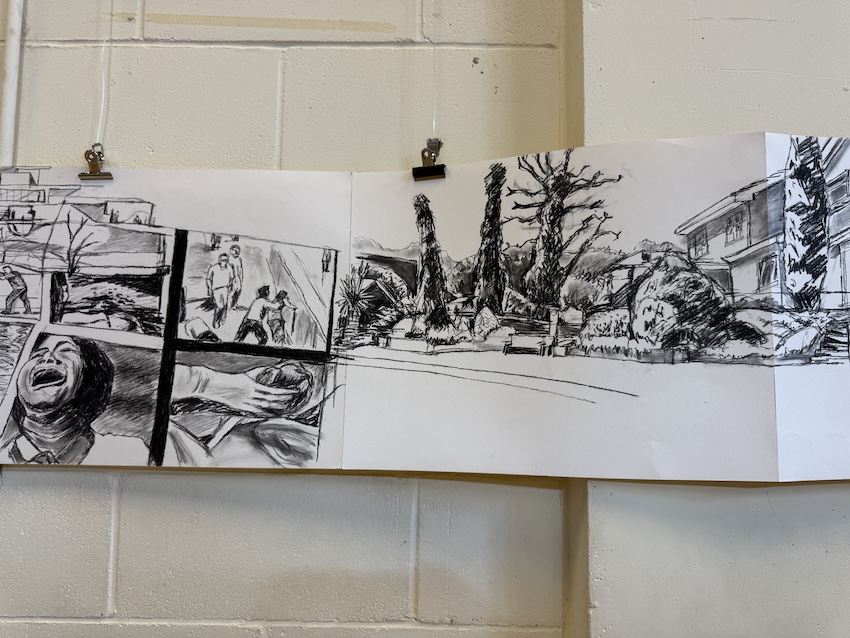

I was conscious of my audience. I thought, well, how would I get people to engage with this sort of anxiety, the nightmares, the kind of imagery that I hope will resonate with others. A lot of the imagery has got movement, a kind of filmic quality, where I try to take you from one image to the next through graphic devices. But I’m also interested in the everyday – I might see an exhibition and I’ll see something that I really like so I’ll take a photograph and somehow inject that into the the whole story, like a woman running up a hill, very epic, so it says something about what I want to say.

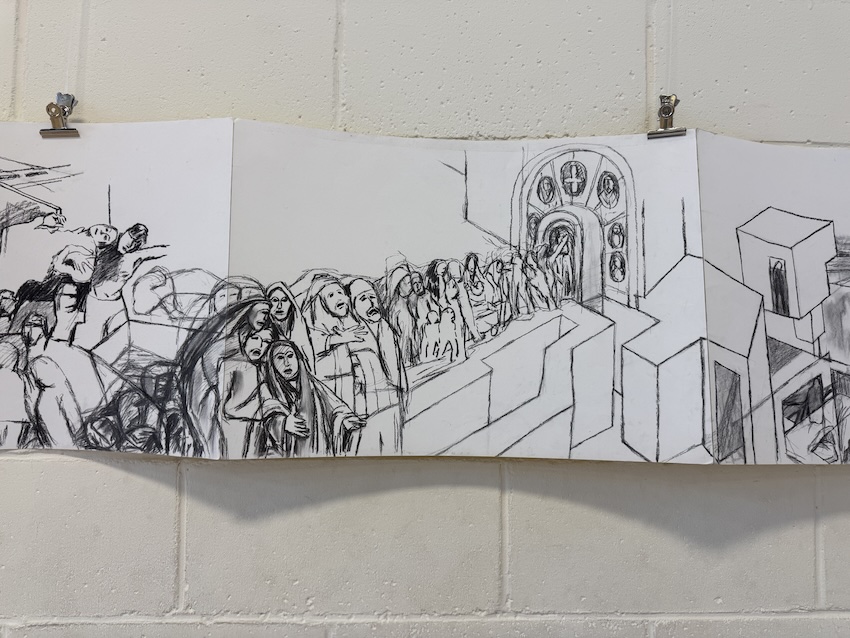

For instance there’s an image of a woman in the series – that’s a famous Mexican actress who did lots of Italian films and she became a symbol for me as part of International Women’s Day. I used her because I thought it was quite a vivid image and then I spliced my bits of religious iconography behind it.

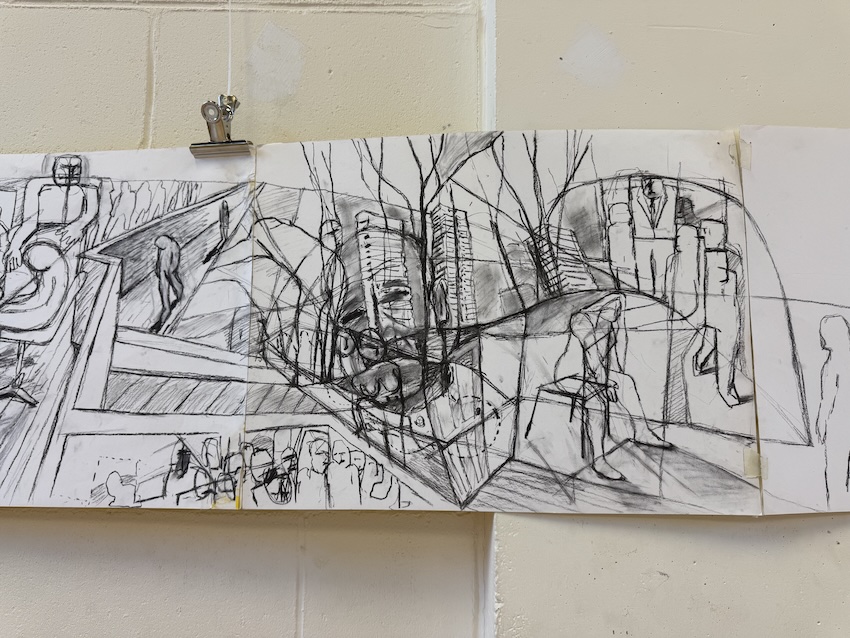

The religious iconography is ongoing – I can’t escape that and what I call “the underbelly” of figures in the world that I inhabit – there’s the ground, there’s the world in which we go to work and and get on trains and look at bills and Excel sheets and things, and then there’s the underbelly, what happens below, the reality of our lives. So those figures are about that kind of underbelly that’s always happening – in my world anyway. And so there’s always people grappling around, scavenging, surviving, doing whatever they need to do to get by.

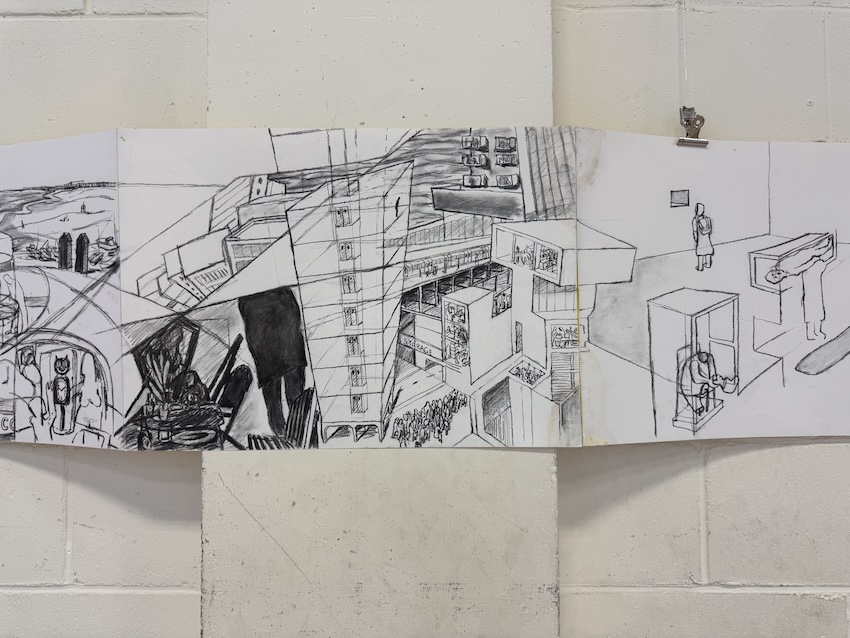

You know it’s my iconography, but I want to reach out to everyone to see if others connect and identify with some of the things that go on in my work. It’s largely my experience – I mean I’m an architect, so you’ll find a lot of buildings. There’s one drawing in the series where you’ve got a building site and all the contractors and the foundations are floating around and then below that you’ve got the crucifix and figures in suits, so it’s merging all those, collaging those and bringing them together.

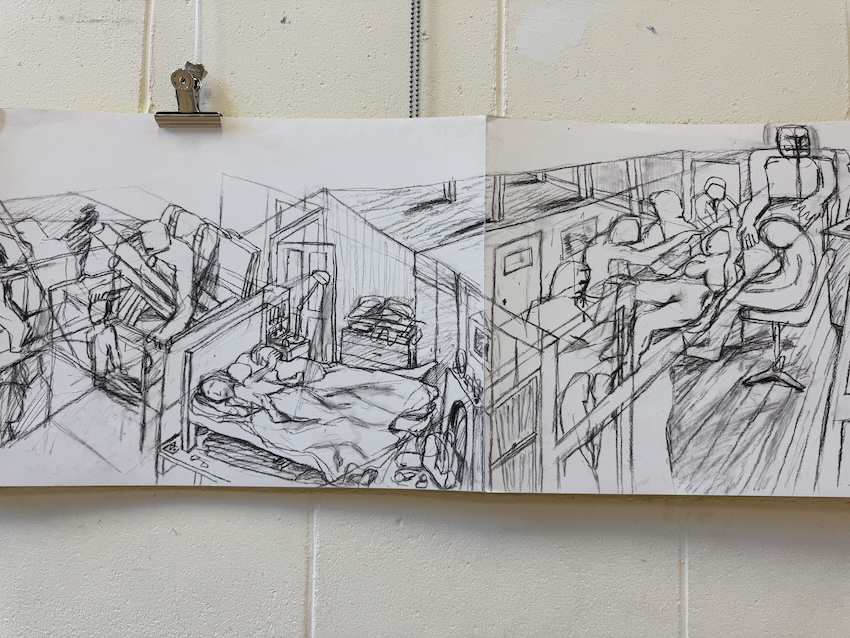

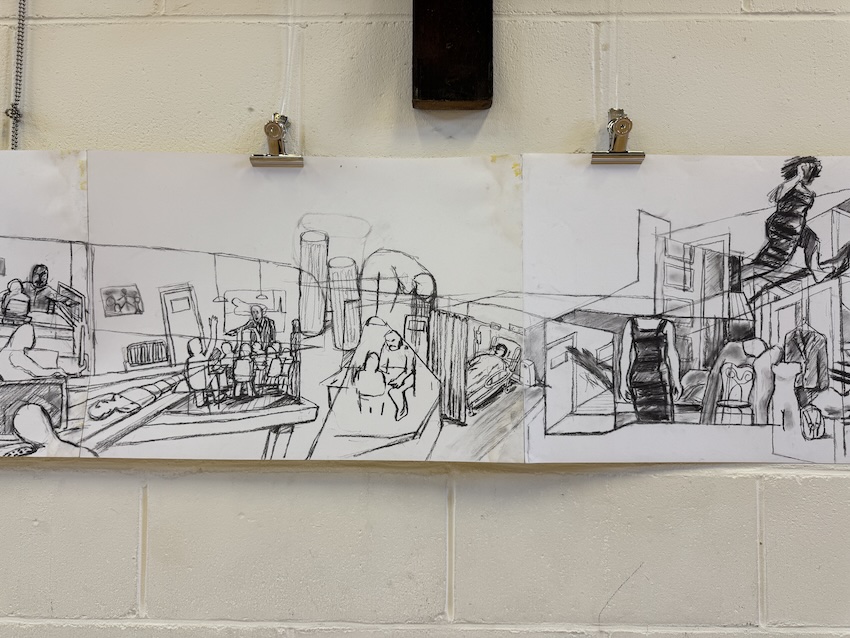

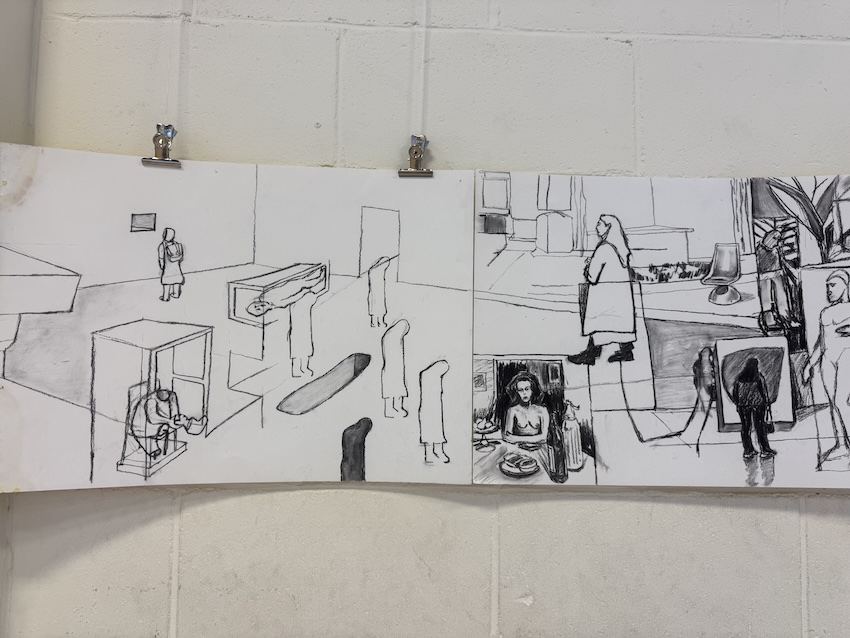

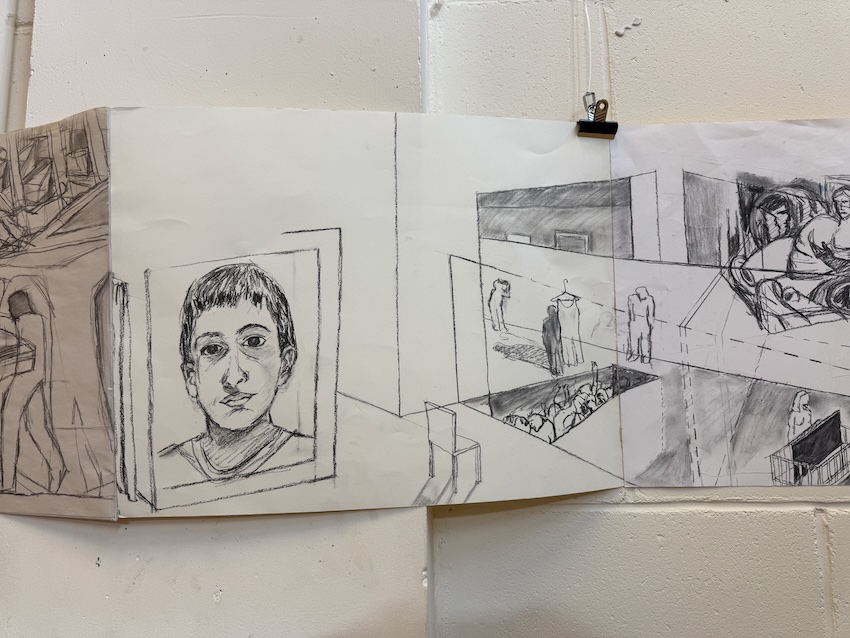

The dreams are a very strong part of how these images begin. Unfortunately, I have some really heavy dreams, like suffocating or feeling hemmed in. A recurring dream that I’m having at the moment is that I’m in a new architect’s office, and I don’t know why I’m there. I’ve got a new position, looks like a senior position, people seem to know me but I don’t know them – I don’t know where my workstation is, I don’t know what projects I’m on, but I’m there, I’m in the dream and it’s like normal. How do you reflect something like that? It’ll be interesting to see if audiences can connect with some of the imagery in terms of what they might say to them – not to me but to them.

“I think the charcoal black and white conveys the feelings of what goes on inside me, really.”

– Chris Christodoulou

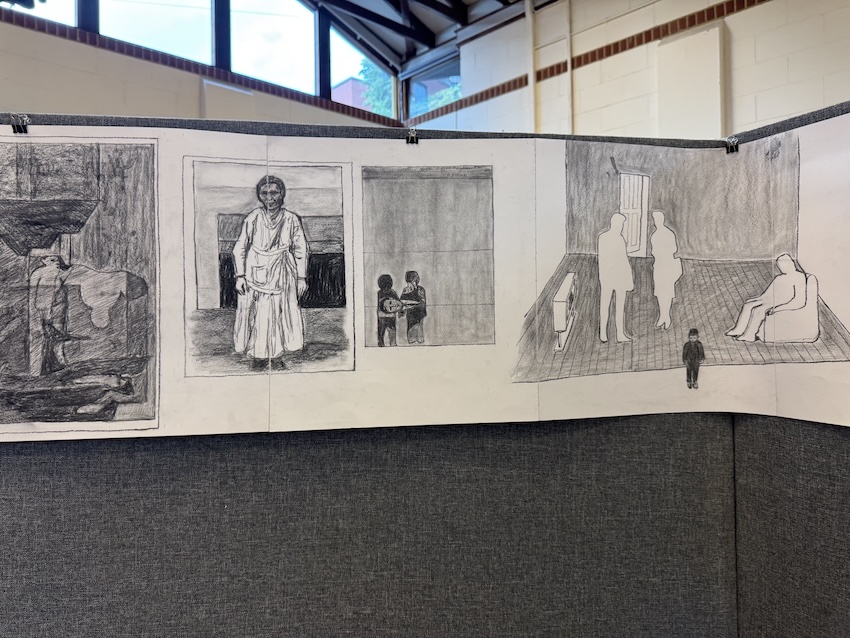

As I’ve evolved over the years things have happened – people have died, my mother died – that become part of the story. Nothing’s planned, it’s about what I’m dealing with day to day, but also what happens around me. All of that comes in. So you’ll find imagery of my mother sliced in with family conflicts and all sorts of scenarios. And they’re part of me working through these issues, and they’re about memory, about loss, about love, the loss of love, death. They’re all there, basically.

SG: Can you talk a little bit more about this relationship between the real and the imaginary? You’ve got the real in lots of different ways. You’ve got the real in terms of work, construction, things that are happening beneath the surface. We’ve got an element of what’s happening in society. We have kind of popular culture with bringing in film stars and imagery like that. You’ve got the real, it’s in family, love, friends.

And then we’ve also got obviously this injection from your imagination, from the nightmares, from dreams, from how you interpret what you see.

CC: Often they’re inseparable, these worlds, and one informs the other. They kind of inspire the other. So I’ll have a dream and it’ll kick things off. But in a way, the reality becomes part of that dream. I’m almost directing the dream. I don’t know if some of you can do this, but you can direct dreams. So I’ll have a dream and then I’ll use that as the basis for exploring other things.

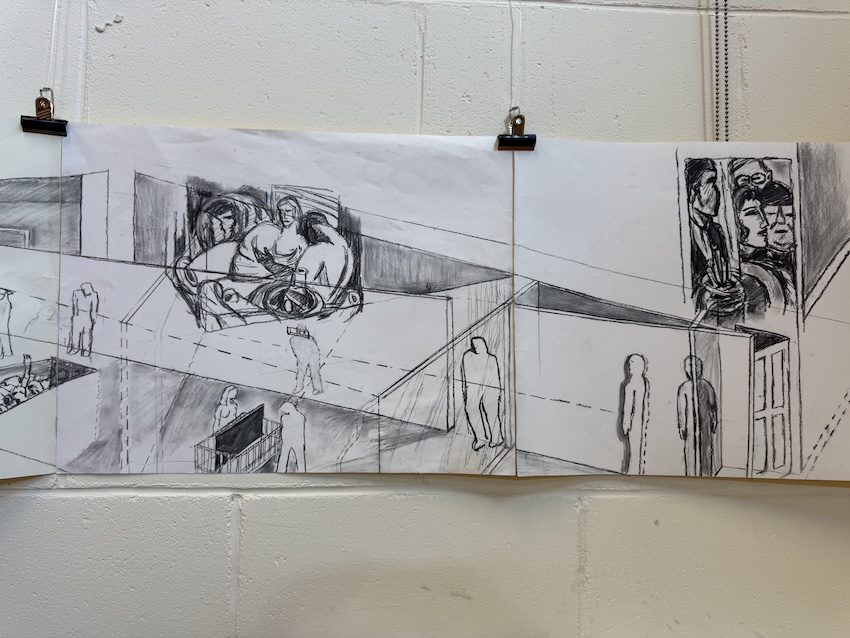

For instance, some of the images you’ll see are gallery spaces. And because I’m not exhibiting these are like a simulated exhibition within the images – if I was going to exhibit in an exhibition space, what would I do? I can let loose, I can do what I like, because I can draw it and make it as fantastical and as impossible as I want. So that’s what I do. I’ll kind of suggest a gallery space and then within that there’ll be spliced in with some personal tragedy or something.

It’s really allowing the dreams to give me license to go where I want to go with them and and to explore what I want to say. It’s like a collage of the real and the imaginary. It’s bringing those two together. Sometimes they begin at different places. It could be the real – a photograph that I’ve seen that resonates and I’ll use that as a kicking off point, or it could be the imaginary, taken from a dream or really loose. They can kick off from either point, but often they overlap and that’s the point where I think it’s interesting for me.

SG: You have recurring dreams and also you are looking at the same thing in real life over and over again, because in our rituals, daily rituals, you’re experiencing the same things happening. What recurring motifs are there that for you carry us through your practice, would you say?

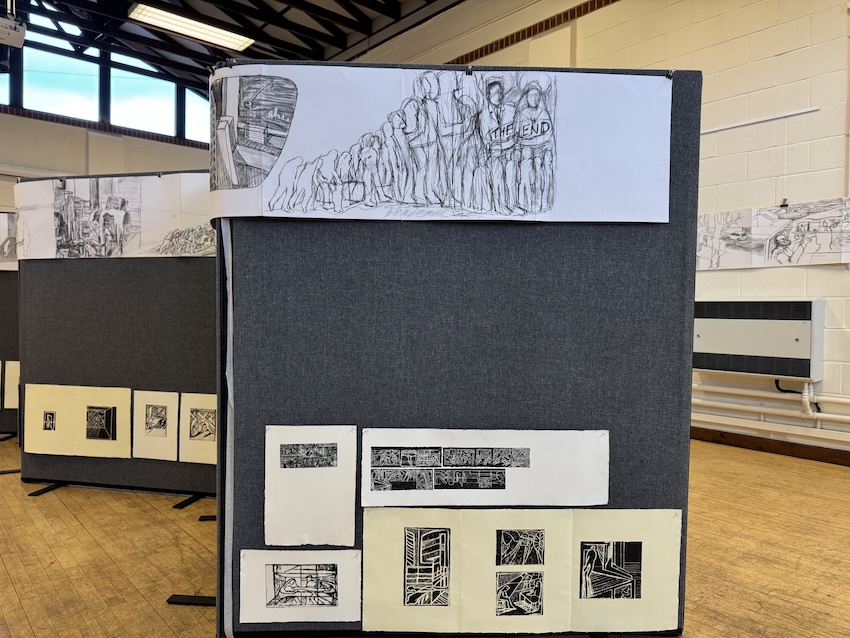

CC: I think when I’m in it, I don’t see it so much because it’s common to me, so maybe other people notice more, but a common motif is a figure always walking away somehow, hunched down, looking as if they’re kind of migrating, or they’re trying to find something, or they’re carrying a suitcase. And it’s either a figure or lines of figures like asylum seekers or, you know, you’ll find they’re around. It’s mainly these figures continually looking for something, but they’re not quite sure what they’re looking for. So that motif is there.

“It’s like a collage of the real and the imaginary. The images can kick off from either point, but often they overlap and that’s the point where I think it’s interesting for me.”

– Chris Christodoulou

There’s a sense of corridors – doors always reoccur, normally a half open door with someone peering through as if someone’s looking at you, like you’re constantly being monitored, being looked at, that feeling. This is the symbolic iconography that I’ve built over the years and when I used to paint they were part of the library of codes that I used. And they’re here too.

If I’m thrown into a situation where I’m given a tight time frame to do something, they’ll come out. My default – whatever I do that’s part of my style – will come out immediately because I haven’t got time to think. I’ll retreat to a particular motif. I bring the figures that are looking for something, moving in and out of corridors, searching, always there, from my iconography.

SG: I think that’s a really good moment to bring in the title of the exhibition, Odyssey, because you are taking us through a journey, through the corridors, through doors, through lines of people, through a figure that is travelling away from us, often with its back to us. Sometimes we see your face. Can you talk a little bit about the title and the relationship to the Odyssey?

CC: I was thinking about a title for the whole series and I came up with “Drawing Nightmares” but I thought no, that’s not going to be appealing to people. People are going to walk away from this. I realised that there are parallels between my journey of homecoming or looking for a sense of home and the Odyssey, Homer’s Odyssey, which is a tragedy of him spending 20 years trying to make his way back home against the wrath of the gods and so on.

It felt like the perfect parallel, and a good reference point. I’m also Greek, so there’s a connection there. I thought Odyssey seemed the right thing, going through all those challenges and being attacked. And that sense of fate. I like that sense that he’s being pushed around by these gods and and in a way I feel destiny. There are things that happen to us in a way that I’m trying to respond to and trying to get somewhere that I’m not even sure exists.

The dream back in the day was, I’ll go back to Cyprus, which is my original home. That’s disappeared now. It doesn’t exist. It’s not just the fact that part of the village I used to own has been overtaken by other people. That’s political stuff that I’m not really concerned about, but it’s more than that. Even our house is no longer there. Our family conflicts have meant that we don’t have a house there anymore. My mother’s passed away. The things that meant something to me are no longer there. I used to go there every year but now I can’t go back. I have ownership of property in the north, which is occupied by Turkish people. Now what’s the use of that? I can’t go and live there, obviously. So this notion of home is always a slippery slope.

“The drawing becomes a journey of exploration for me.”

– Chris Christodoulou

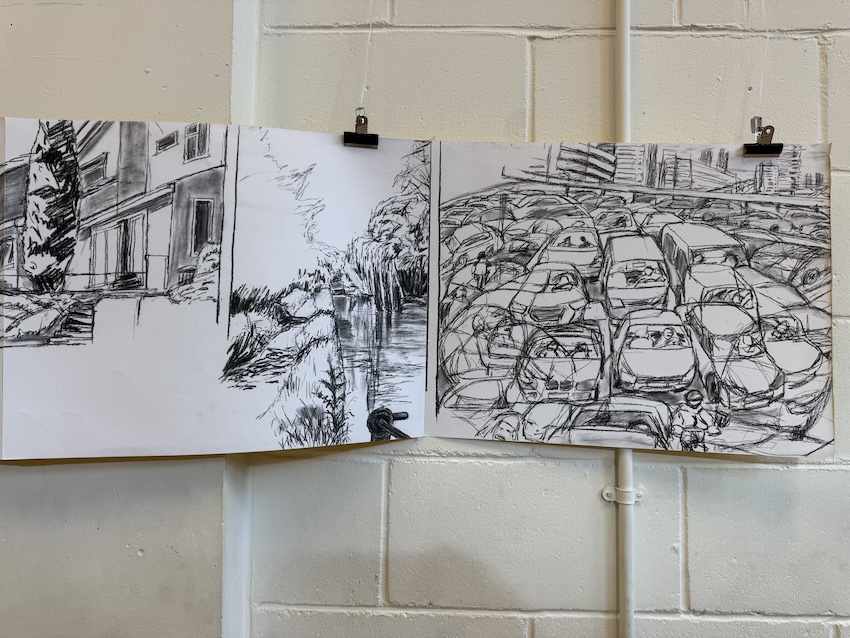

We live in a flat at the moment, and like most of the nation, looking to move somewhere where we can live more comfortably, but it’s impossible. You’ll see lots of images of estate agents in this series, holding banners for sale. That’s where that piece of the puzzle comes from. It’s me saying, well, look, it doesn’t work. You can go searching for homes, but the reality is most people can’t afford to move away from where they are.

All those notions of home all coincide – the home in Cypress is no longer there, the one we have now or forever is not good enough, it’s collapsing, in fact, so there are roofs collapsing and things collapsing – this sense of decay and collapse over time is also a metaphor for what’s going on. These images are all about that. They’re not simple images. They are about everything. This is my way of trying to deal with it and tell that story and hopefully make some connections with other people that go through similar experiences.

SG: A lot of the time, the work is sending us out into the world. We’re following something. You’re looking for something. Are there moments in the work of clarity where you’re stopping and you’re turning towards us, turning towards something rather than turning away? There’s a self-portrait for instance, and next to it we’ve got the turning away. But what prompts this moment of turning towards something?

CC: That’s me staring at, almost trying to… it’s difficult to convey. It’s me saying, this is my work, this is me, the reality of me. It’s not like a selfie photo. It’s just me, the raw edges, with warts and all. And I’ve got a wart there on my left cheek as well. I’m saying, well, this is me. Have a look at me. I’m not going to be here forever. That kind of thing. And this is my world. Yeah, I guess it’s almost like…it’s not a pleading but it’s asking for acceptance.

SG: And recognition? Recognition of self, of humanity?

CC: Yeah yeah yeah, this is me, hopefully you can accept me, yeah, and recognition, so peering out – you’re right, I never thought of it in that way, I’m often looking the other way, going away from things. That’s me, just peering out to say, “This is my world, do you accept it?”

SG: It very much connects us to the work more deeply by being able to connect with you. Looking at somebody’s face is a very intimate experience isn’t it?

CC: It is and I’m glad you picked that up. It is true it’s me saying “This is me looking out to you” but it’s not a vanity portrait as such. It is exactly that, looking out, because then that can get too self-indulgent in a way. But there’s so much else going on, there’s only a few incidents.

It’s also self-reflection as well. Van Gogh did lots of portraits, he was always searching to get the meaning of how he was feeling. He was going through so much passion, and how did he deal with that? He was forever trying to share that passion, you know, through his expressions in his paintings. So it’s kind of like that. If I had to squeeze up all these drawings into a portrait, how would I do that in one image? It’s difficult. I’m really glad you brought that question up as I wouldn’t have thought of it otherwise but now you’ve asked it, yes. In a way it’s reaching out. It’s reaching out.

SG: Do you have a favourite bit of this drawing? Or does it change?

CC: I have parts that I quite like, processional parts where groups of people are moving into doorways or tunnels or whatever. I quite like the one on the invite, because it’s got the scale of it and it has a sense of movement. I like images that have a sense of movement, that move in and out. So I like that one. And then I quite like the Mexican actress piece because also graphically it’s quite dark and it’s got some of my older iconography of priests and archbishops. It blends the ideal and the underbelly.

SG: Was that fairly early in the series?

CC: That was fairly early.

SG: How does it feel when you look back on the earliest pieces in the series?

CC: Well I can be realistic, the earlier ones were really rough and almost sketchy, like someone would sketch. But I don’t mind that. It’s part of the process. Whenever anyone does anything, you start off and, even if you’re putting on a play, your first performance is very different to the last one or the ones in the middle. You start off and it’s all a bit clunky, things are going on, it’s not happening.

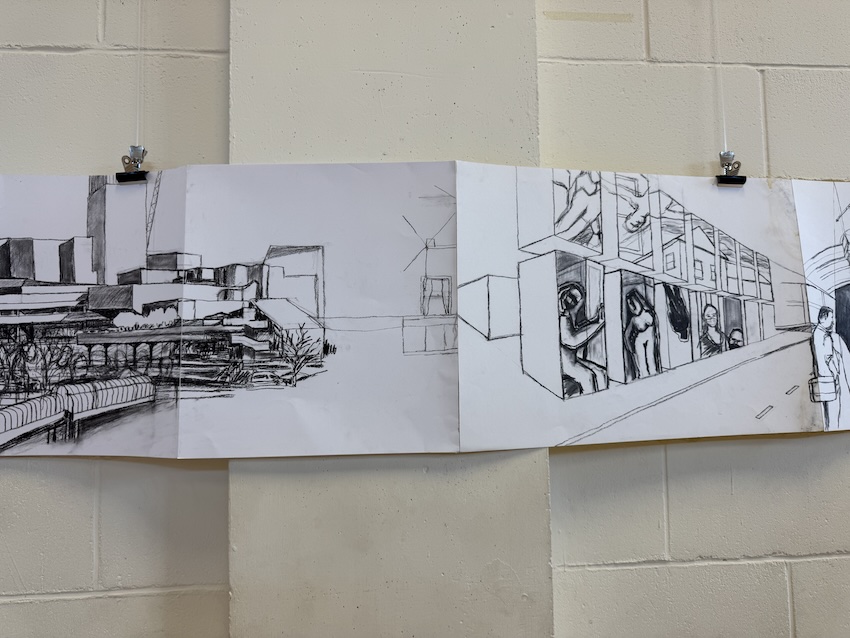

But as I progress, I become more confident with the imagery or allow myself devices, like where I’m suffocating, in the images, which are quite strong, I find, and then there’s the urban jungle, how that comes into everything. I quite like a lot of that. I mean, I like the realistic ones like the South Bank and so on, but it’s not because they’re realistic, it’s because they’re part of where I live – you could say I’ve lived half of my life at the South Bank, drawing, so it’s part of who I am.

SG: How do you know when to stop? How do you know when a particular section is finished?

CC: Normally, I get tired. It’s simple. If I do three, four panels, I’m doing three, four, five hours. I get tired and if I carry on, I’m forcing the issue. If I can address a particular dream or sequence of thoughts, then I’ll leave a drawing half open so that next time I come to it, I’ve got an idea where I can connect. I remember where I was and visually I can either carry on with the story or continue another story and just use the graphic devices to connect it all together.

In terms of the whole thing, when do I know? I don’t. To me it’s an ongoing project and I’ll only stop when I feel it’s not saying anything, if I get bored with it.

But what I’m doing also is evolving the drawing into other forms to bring it alive through animation. I’m doing animation, taking clips of certain elements within the drawing and making short clips, so that’s having a secondary thought and also thinking of ways of creating installations around the drawings.

SG: That ties in really with your architectural background as well. What kind of influence has your architectural practice had on the drawing?

CC: From a compositional point of view, they’ve got that kind of dynamic, the perspectives that you find in architecture, the images have some of that and they’ve all got vague titles – there’s a South Bank one, there’s a Falling Waters one by Frank Lloyd Wright – so you’ll see references, but also the way in which the compositions are staged to create movement and to seduce the spectator into the image to get them to follow the imagery around. The architectural three-dimensionality does help in generating those images and thinking about them in that way. Almost like a film, a filmic scene, like a storyboard in a way. So people feel like they’re cutting segments of films and tagging them along.

SG: Can we talk a little bit more about then time and specifics? Because you started it at a particular time and we’re through to the present day now, but you don’t include the date or the time on the drawing itself. So although it’s diaristic, we don’t know when, we don’t have a sense of when the specifics were for you. Is there a reason for you to not include those things?

CC: It’s because I think those feelings would have gone way back. It just happened to be then that I decided to actually try and exercise those feelings. I would have had those years back, so a lot of these motifs go back to way beyond my experience. I’ve been working in architectural companies for about 30 years. You could literally pin some of this information onto what was going on 30 years ago, you know? So in a way, the linearity is good in terms of seeing a succession of things but where that begins and ends is not as critical.

There are clues obviously to chronology in terms of my mother’s passing and things like that but other than that I don’t think it’s important really. If anything it may tie back to certain events in global culture, you know, like COVID – you’ll find there’s some masks in there – which give clues to where we were but I don’t think specific dates are important. Do you think it’s important?

SG: No, I just think it’s an interesting relationship with the real and the imaginary and it takes us a bit more into the land of film. You were talking earlier about storyboards and film, that you’ve created a space for us to have our own feelings and desires and hopes and thoughts around it. But on the film side, the storyboard side, why is it black and white? Do you dream in black and white?

CC: I think I dream in colour and black and white. I do both. But it’s not just black and white, that’s for sure. I think, firstly, some of the elements are dark, you know, that I’m trying to convey. But also I find colour is another dimension of consideration you have to think about, and if I have to think about something too much, then it becomes a self-conscious exercise.

I’m not saying that you can’t do it with colour, you certainly can, but I find it’s a lot easier for me if I use black and white. Somehow the darkness and the shadowy nature of the world that I inhabit is evoked by black and white, because it’s about shadows, about things hiding and coming in and out. Or things we can’t see. The shadows are important. I think the charcoal black and white conveys the feelings of what goes on inside me, really.

“It’s about shadows, about things hiding and coming in and out. Or things we can’t see. The shadows are important.”

– Chris Christodoulou

I do love colour. I have used colour back in the past, but it’s a different dynamic. You have to think about the relationship between colours and how they work so because I want the drawing to be more spontaneous, this way works best for me. But I’ve seen it work also with colour. People can be just as expressive in different ways.

SG: Can you recommend an artist who works in colour to us?

CC: Max Beckmann‘s a German expressionist who starts his paintings with a black background. Most paintings have a background colour like a pink or beige or whatever. His background colour is black. So he’ll start with a black and then work his way out from that, which is interesting. That’s why I probably like his work.

SG: I’d like to see you working on black paper with white chalk.

CC: I have done that, but only as an exercise with students. I haven’t dared to do it on my own.

AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Audience member: Do you think you’ll continue?

CC: I think so, but if I find I’m getting stale or I’m repeating myself or feel like it’s not doing anything for me, that I’m not going through something, a journey of realisation, then I’ll stop. No, actually I won’t stop, I’ll evolve it, like I said. It’s turning into an animation and then soundtrack and narration possibly. So it becomes something else. A different form.

Audience member: And another question. Did you just follow the process? Were you always satisfied with what you’d done or did you ever try again on one particular drawing? Or was it just trusting what you were doing was right?

CC: It’s a good question. I mean, there’s a lot of thought that goes in before I start. So I do a little doodle with a pencil, almost like a storybook, to plan out a section – I’m going to put the goddess over here and maybe this over here and then imagine it in my head and then go for it. Most of the time it works out.

I can honestly say in most of these, there’s some that are less impacting than others that I only realised looking at them when we laid them on the floor and I’ve had Sarah, the great critic that she is, point out in a very polite way, no that’s not quite right or it’s okay, but it’s not really tying in with the rest and it’s not as strong, you can see it’s quite formulaic and so therefore it’s chucked into room 101, you know, to get me thinking.

So I do it and leave it and then come back to it because whilst I’m doing it, I’m so in it, I can’t see the wood for the trees. I’m sort of so obsessed by getting the nightmare out, as if that’s the end and all of it, that I might not see what it actually is from the outside in.

Audience member: So you’ve not seen it in its entirety before, only in sections?

CC: Exactly, I’ve only seen it in sections and in portfolios and bits and pieces, so this is the first time for me, seeing all the drawings together as a series. And I haven’t actually gone round it to see it all yet.

Paul: How does it feel, Chris, confronting the psyche when you see the work like this?

CC: It’s more how you feel – I’m more immunised by it, I’m immune to my own smell

Paul: But does that keep you isolated in your own vulnerability?

CC: Not really, it begins I can get on with the kind of challenges that I have and what goes on in my head. If I can put it out there then I feel I’ve made some contribution in my mind, this is my way of saying something in the world. People go and write books or they compose a bit of music – I do this drawing and try and make a connection with people. And like a book, I hope someone can read these images and identify them in some way or get something from them. You don’t have to be an expert artist to engage. It’s just about connecting with your own life and see whether it resonates.

Paul: There’s a lot of female images in distressing situations, and then especially when you get to the Mexican actress, it’s like she’s like a symbolism of hope for you that there is joy in a female form.

CC: It’s not so much the female, it’s the ideal. Not a form, it’s the ideal. You know, someone that cares for you and you care for them, to be loved. The female form is just there as a symbol. The forms are symbolic of the unattainable. In other words, it’s there, you’re always searching for it, that’s what we’re looking for, really. It’s not objectifying the woman, she’s there as a symbol of the ideal.

Paul: I understand because a lot of people have conflicting relationships with male and female, so I just think it’s really very honest of you to be able to express and feel comfortable in your expression that there is this confrontation with female images that comes from the maternal form, the mother. Has a female ever lived up to your mother’s image? Because we’re all chasing our mother’s love, aren’t we? And even if it’s validation, if it’s love, that doesn’t mean constructive love, it could be validation for the love that she never gave.

CC: You know, you’re not far wrong. You’re on the right path and there are very credible thoughts there and in some ways these figures are about that sense that we’re all searching for that. Whether that’s represented by mother figures, we’re looking for something to embrace and make us feel right and that we’re wanted and whatever. It’s part of that. The question you have to ask is, is it present in the author’s drawings or is it my interpretation of the images? Am I searching for it and how, in what form? And then the next question is, well how does that relate to me? Am I forever looking for that? I’d say explore it further in terms of what it means for you because it’s not just about me.

Paul: Oh no, it’s people in general. I happened to be studying a bit of Carl Jung, and in relation to this female validation, he calls it the maternal shadow of individuality. We idolise the goddess as a mother, but the mother can’t always be perfect because she’s human. But because we symbolise, like I say, the perfection that never was, we’re in confliction until we face up to the shadow of that individuality and appease ourselves that our mother wasn’t perfect. It helps us to appease those shadows.

Because I agree with you, this is a two-way thing. This is definitely not a projection on you as an individual. Like you said, it’s great to share because it makes you understand and appease your own psychic vulnerability, that no, this is not you. This is actually a great human triangle.

CC: I mean, hearing what you have to say, it’s very much meaningful. It makes sense. And in a way, I haven’t psychoanalysed it, but what you’re saying seems to really connect with what’s going on, so, you know, it’s going to make me want to look into that even more. But you’re right. There’s an element of that. We’re looking for our mothers and in a way they’re not the ideals that we make them out to be. And so on. But it’s just a form of looking for an ideal that maybe doesn’t exist. That’s the point I’m trying to make, that we make idealised things.

Paul: The train’s coming down the tunnel, the end is like a pursuit down a path, that there’s no end to that path.

Sophie: Did you ever bifurcate or have you cheated? I’m not sure that it’s all one line and I wonder whether at times you’ve kind of gone back to an earlier one and took it to another branch rather than always continued?

CC: No, I’ve always continued apart from in the last few months where I’ve adapted it for the animation. So I’ve taken one branch, as you said, and then started animating it. And so the way it’s joined up somewhere else has been somewhat engineered to make it work. So there are instances of that, but largely, most of it, it’s all been continuous. It’s only in the last few months where I’ve tried to incorporate animation into it.

And even then, it’s been within the drawing. So I take a figure, do stop motion, animate it, take it somewhere else and then you see the path of that animation, ghosted leftover trace of that animation within the drawing as it is. So you’ll see it in the screens here when you walk around, you’ll see remnants of the animations. So yes, good question. But no, very, and this is why when we were looking at it, we could see some of them are not as strong as others. And so because I haven’t had time to look back, it’s just gone on.

I like the sections, but then you’ve got to see how all the sections tie in together as well. But yeah, I haven’t forced the issue in any ways.

Hassan: How’s your son Alex? I can see the sketches in there.

CC: As you know, he’s as prolific as me, if not more. He’ll be doing his own version of these. So he’s good and he inspires me too. I have a child that I love and wife and I love them. So all that world is part of this world. The architect, the artist, trying to not balance but try to keep them all going all at once.

Oliver: I was just thinking of the oscillation between anonymity of the figures, they don’t come out as, or someone even lose a head or something. There’s quite a poignant one, I was looking for it just now, I lost it, but it’s an exhibition where the people are looking away and down and there’s no features and there’s a sense of alienation. And the oscillation between that and graphically coming out with the face, then going back to anonymity and ghostliness.

And also the spaces themselves seem to have a kind of anonymity about them, they’re not domestic. There’s that sort of sense of being in a world, well it’s the home thing, looking at where do I belong. We were talking about this before, to extend that, where do we belong on this planet anyway, but there’s also the cultural belonging, there’s the refugee status, all these sort of things that go on.

So it raises a lot of questions and I think they’re wonderfully animated and I think if you did it in colour it would slow it down somehow. It would somehow slow the eye down. I think they sort of move in this way, undulating way.

CC: I think what you’ve just said has caught the essence of it. How that sense of space is alienating and coming out into the more familiar kind of visuals. It’s all part of this in and out, of trying to take the spectator in and out. But what you’ve just said has really captured the mood of what I’m trying to get. This sense of figures, they’re either being crushed in congested tunnels and unable to breathe, or they’re isolated figures in the middle of nowhere, searching for something.

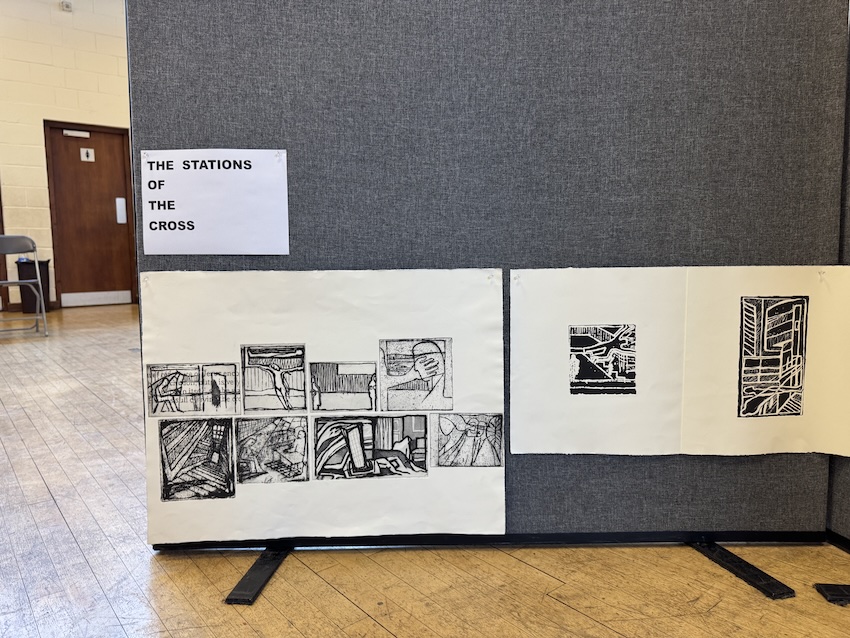

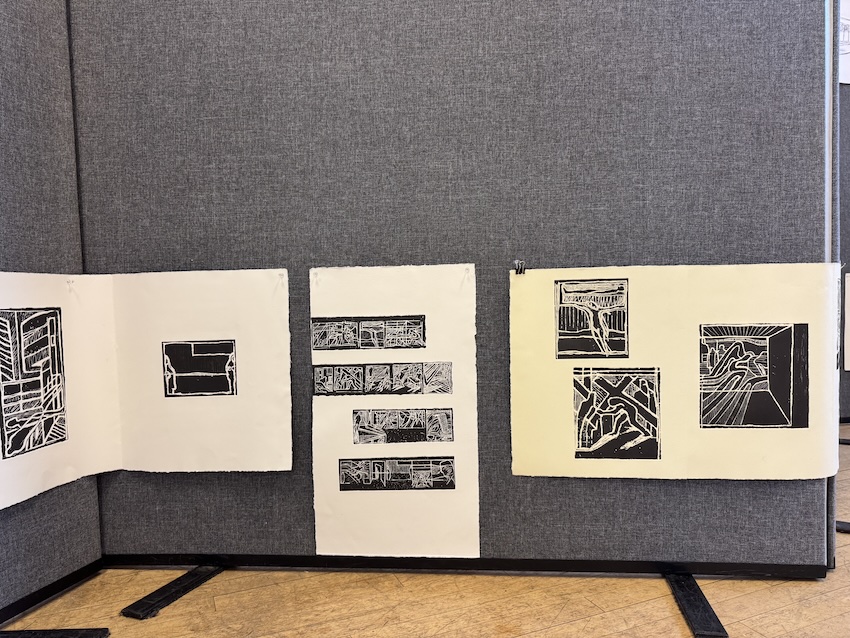

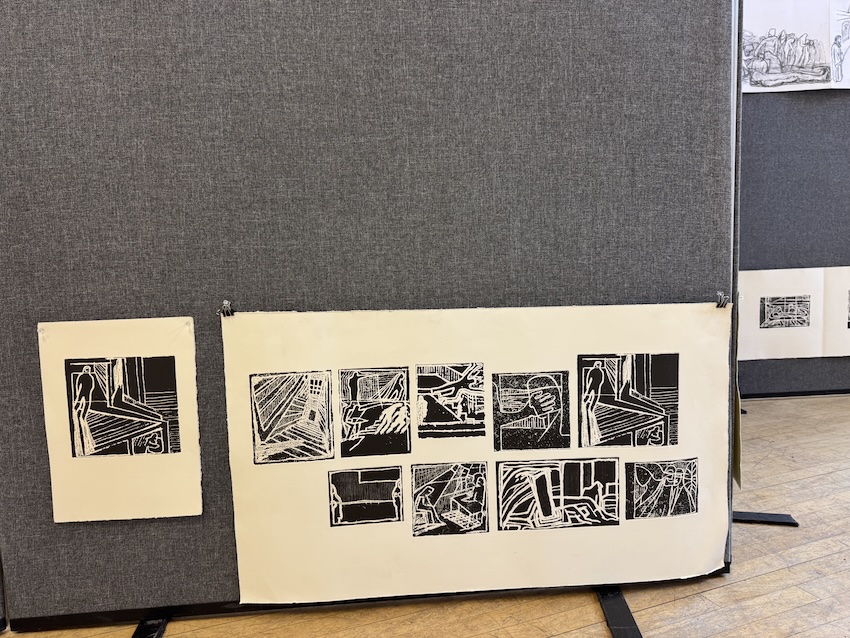

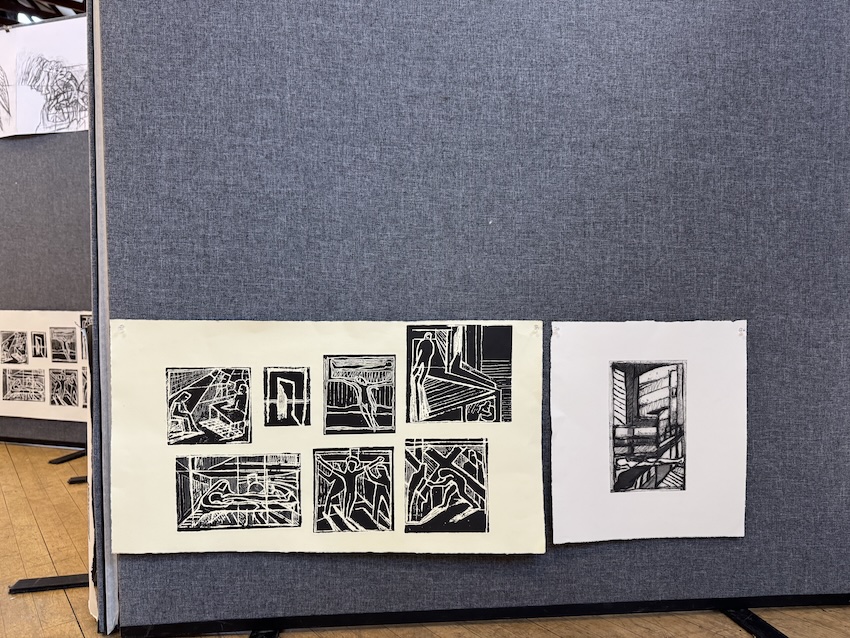

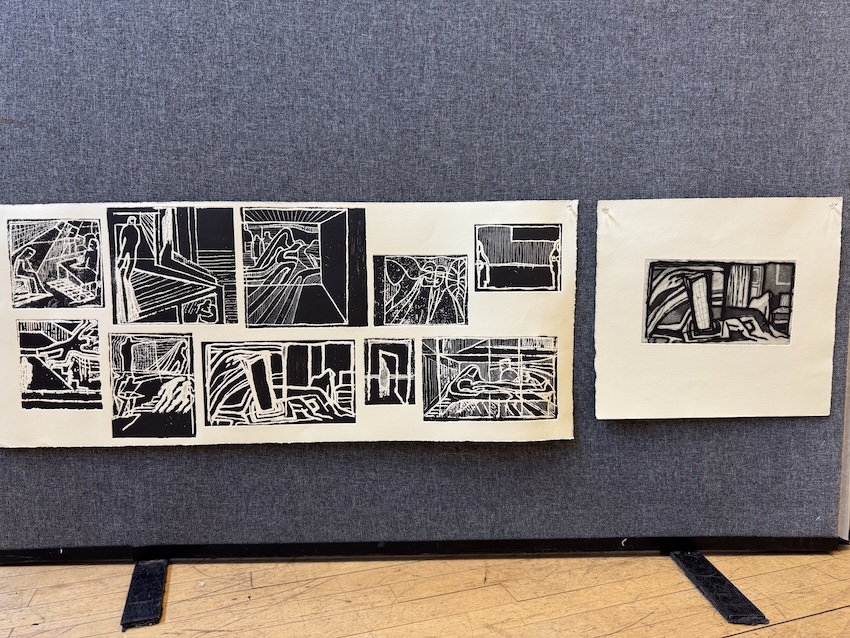

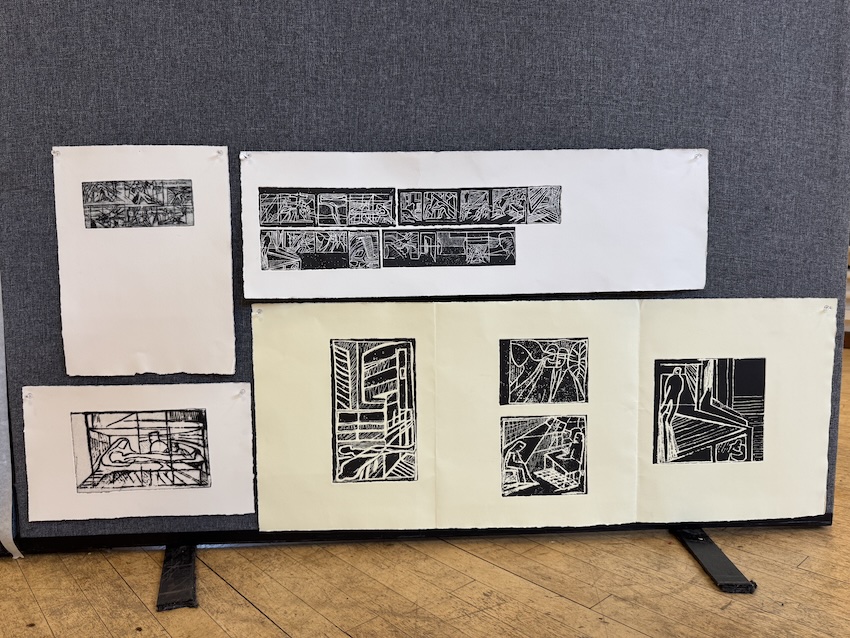

Ziqi: I think the drawings are wonderful but I wanted to know more about the prints too?

CC: They are Stations of the Cross. If any of you know your religious text, Christianity, there’s 16 of them, and they’re the Labours of Christ. I did these about 15 years ago at Morley College – I saw a biblical text and it was in Times New Roman, very biblical. I took a photocopy of it and then on that text I doodled my ideas because I do a lot of doodling. I get a newspaper and suddenly I find I doodled it to death. There’s images and things all over it.

So I started with those photocopies. The script was actually of the Labours, of the Stations of the Cross. Each one was described in biblical text and against each one I did a doodle, and that doodle was really my urban nightmare-type interpretation of that scene, of Christ carrying the cross or Martha washing his feet on the cross. And it wasn’t humanised, but almost a kitchen sink version, of what would I do, in my modern context?

Then these sketches, as always, they grew and then I enlarged them, photocopied them, enlarged them, and those enlargements became these images here. These are etchings with some aquatint, but they’re also the reverse, because they’re relief printed as well. It was such a strong bite, open bite, I actually rolled colour over the top and they became double reversed. I’d like to show you the originals one day so you can see the small prints.

It’s a really good question because a lot of my work kicks off being very small and then it grows into something else. If I have the time and space, which I don’t anymore, it becomes an installation somewhere, but it grows from something like this that becomes bigger, becomes a model, the model into sculpture, and then probably an installation – that’s my perfect process but what you’re seeing is the middle process here.

Sophie: I think you found something here. I’ve seen your prints for a long time and I’ve liked your more literal drawings as you know, generally, but I think in a way this has enabled me to see more of a – I don’t know – I used to find one single sheet of one single nightmare not completely convincing, whereas this is really kind of a completely different animal. You really found something which I don’t think I’d seen – the continuity, you keeping at it, but also the changing but recurring – that becomes a completely different thing than a single image. I think the single image works less, but this is kind of really interesting.

CC: Following from that, I’ve realised that too. And what I’m doing is going back to prints and using the same method of joining up the prints on a smaller scale to see how that might generate, you know, sort of a composition. So I’m trying that out, but they’re smaller and they might end up being fold-up books or something, but it’s allowed me to explore.

In one’s creative journey, you always go back and forth. People go back to painting, they come back to printmaking – one informs the other. I’m going back to printmaking and also following up the animation. So it’s opened up a whole new world, whole new ways of looking and pursuing the work.

Chris's exhibition details

Stalactites of Memory

An exhibition of linocut prints from Trinidadian printmaker Lee Johnson.

More Features

All featuresEtching

Etching was originally invented as a method for adding decoration to armour during the Middle Ages. Artists began to use metal plates for printing in the 15th century, when Albrecht Durer made work on iron plates. Later artists such as Andrea Mantegna in Italy and Rembrandt in Holland went on to make etchings on copper.

Soft ground

Soft ground was invented in the latter half of the eighteenth century as a means of reproducing the grainy qualities of chalk work. It was first used in England by Gainsborough and artists of the Norwich School.